Reaping ripe: The story of why we celebrate harvest festivals

The next time you shop for some food — even simple vegetables — mark your emotions. You might experience an inexplicable sense of happiness while laying out the veggies in front of you.

You might also follow this up briefly by talking about them. You could also feel a strange sense of achievement when the effort symbolised by your shopping basket is recognised.

Psychologists and evolutionary scientists explain this emotion as originating from our ancestors who were hunter-gatherers. (Psst: Do ask your psychology teacher for some more info on this interesting point).

From foraging food to farms hardly

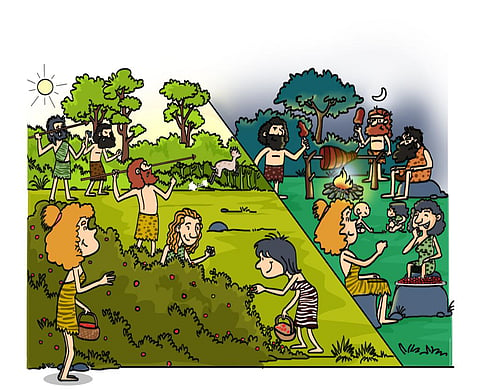

10,000 years ago when humans did not form a settled society, the early men and women spent all day foraging for food. At the end of a tiresome exercise, it was their foodstuffs which comprised the high point of their entire day. They usually celebrated this excitement through a gala dinner among their group — or call it a harvest festival for every day!

Such partying could well be the origin of many harvesting festivals that we now celebrate with great pomp and gaiety. The only difference being, that unlike the daily Stone Age dinners, we now celebrate only the first crop harvest of each year.

The practice of observing such annual or periodic festivities evolved over countless years along with our agricultural developments.

Humans started settled cultivation around 9,000 BC. Then onwards, the pre-historic people developed their farming according to seasons and specific crops. In the Indian subcontinent, two monsoons blessed the flora, thousands of fruits and vegetables flourished the forests, and weeds like paddy colonised the landscape. Thus, eastern India became one of the first places on the planet to domesticate rice.

Over the centuries, humans undertook selective cultivation of several wild crops, fruits, and vegetables. Their cornucopia forms our current agrarian world and sustains over seven billion people worldwide. Many peoples’ and tribes still collect the undomesticated, wild food plant varieties and even have a set calendar or season to do so.

Fun and frolics far and wide

Harvest festivals are quite a commemoration of our evolution into a settled agrarian society.

A conservative listing would have nearly 3,000 such fests being observed around the world; India alone has over a hundred of them.

There is not a single country across the globe that doesn’t honour its harvests. Nor is there a single community that doesn’t celebrate such fetes as major cultural events. But their geographical distribution offers interesting aspects: The richer the biodiversity of an area, the higher are the number of its harvest festivals.

Example: In Arunachal Pradesh in India, the Adi tribe feasts during some 13 harvest festivals. This is understandable as Arunachal is one of the most biodiverse places in our country. Similar is the case of forested states like Chhattisgarh, Odisha, and Jharkhand. Over there, one would find a range of 10-15 such festivals, each representing varied agrarian aspects. Their get-togethers could symbolize the first harvest of a particular food grain, the first day of consuming a particular fruit or vegetable, or even mark the beginning or end of their farming cycles.

In case you did not notice anytime earlier, in most Indian states, there is a day when people celebrate the first harvest of mango when it is offered to the gods. Similarly, there are first-eat

festivals for radish, beans, pumpkin, and nearly all the major fruits and veggies which are eaten and enjoyed in different parts of our country.

Thus, in a way, the harvest festivals of a region serve as the agricultural diary of its local communities.

That is why wherever you go, certainly find a harvest festivity.

Consider this: In May-June each year people in Bali in Indonesia gather for their rice harvest.

In August-September, the Ewe people of Ghana rejoice the arrival of yams, a major crop, after the end of their rainy season. In October, Thanksgiving, a major harvest carnival, is a time of merrymaking in Canada and the United States.

In India, too, from January onwards, we have a series of folk harvest festivals known by varied names. I’m sure you would’ve heard of Lohri, Makar Sankranti, Baisakhi, Onam, Pongal, Uttarayana, Khichdi, Shishur Saenkraat, and Magh Bihu.

The Indian harvest festive season starts from Makar Sankranti, which usually falls on January 14. This day marks the first day of the Sun's movement from the Tropic of Capricorn towards

the Tropic of Cancer. In other words, it marks the waning of winters and the onset of summers in the northern hemisphere, where India lies.

Thought for food

Most crop festivals are predominantly about paddy. Further, most of these occasions also mark an ‘auspicious’ period in which people prefer to fix marriages or similar significant life events. Such a crop-reaping period in an agrarian society is also a time of thriving commerce. That’s when the prosperous and effluent sections tend to spend exuberantly. In fact, not so in the distant past, schools around the country were also closed for what was known as the ‘harvest holiday’—to enable little kids like you to jump with joy.

In fact, apart from the yield, many tribes also celebrate the collection of seeds after their crops are reaped.

These lesser-known festivals are hardly documented but their celebration can still be noticed in remote areas. Recently, the Kutia Kondh tribe of Kandhamal district in Odisha revived their ‘Burlang Yatra,’ a fair held in February-March that focuses on the seeds of millet, their staple crop.

All these festivals usually involve worshiping the land, honouring the farm tools, and reading the panchang. The panchang is the traditional Hindu calendar, based on the movements of moon, and holds importance for our agriculture. It is often referred by farmers to plan their sowing and reaping season, learn about the weather and potential climatic events, plan harvest, etc.

If you map the agrarian festivals of India in the Gregorian calendar, it will overflow by nearly three times with the number of festivals we celebrate per month across our country!

And if you look closely at these fests, you will know exactly how our food ecosystem is closely integrated with our seasons and climate.

So, more than celebrating our agrarian heritage in the harvest festivals this year, let us express our gratitude to our Mother Earth who provides us for the very food for our survival.