India’s new climate targets: Bold, ambitious and a challenge for the world

India’s commitment to achieve Net Zero emissions by 2070 is akin to not just walking the talk on the climate crisis, but running the talk.

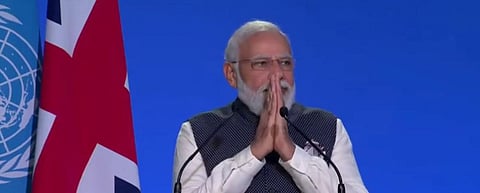

At the 26th Conference of Parties (CoP26), Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared a five-fold strategy — termed as the panchamrita — to achieve this feat. These five points include:

- India will get its non-fossil energy capacity to 500 gigawatt (GW) by 2030

- India will meet 50 per cent of its energy requirements from renewable energy by 2030

- India will reduce the total projected carbon emissions by one billion tonnes from now onwards till 2030

- By 2030, India will reduce the carbon intensity of its economy by less than 45 per cent

- So, by the year 2070, India will achieve the target of Net Zero

India’s climate change targets are laudable and put the ball firmly in the court of the already rich world to now show that they mean business. This is because, India has not been a historical contributor to the greenhouse gas emissions — from 1870 to 2019, its emissions have added up to a miniscule 4 per cent of the global total.

It is lambasted as the world’s third highest polluter in 2019, but its scale of emissions, 2.88 CO2 gigatonnes (Gt) as compared to the highest polluter (China at 10.6 Gt) and second highest (United States at 5 Gt), are not comparable, not by a stretch. And, we have a huge need to grow our economy and to meet the energy needs of millions of our people.

So, from every angle, we did not have to take these global targets to reduce our carbon emissions. This is why, it is not just a challenge to achieve for India but also a challenge for the world to follow suit.

But, what do these ambitious targets mean? Let me decode them:

- 500 GW of non-fossil fuel energy capacity by 2030: India will meet this target

India’s Central Electricity Authority (CEA) has done a projection for the country’s energy mix for 2030. According to this, India’s installed capacity of non-fossil energy for electricity generation — solar, wind, hydel and nuclear in 2019 was 134 GW and by 2030 it will be 522 GW. This will require solar energy installed capacity to go to 280 GW and wind energy to go to 140 GW.

According to this, total installed capacity will be 817 GW and power generation will be 2,518 billion units in 2030.

Under this scenario and energy trajectory, India will be able to meet its 500 GW of non-fossil fuel energy capacity by 2030.

| Installed capacity (GW) 2019 |

% | Generation (Billion Units) 2019 |

% of generation 2019 |

Installed capacity (GW) 2030 |

% of installed capacity 2030 |

Generation (Billion Units) 2030 |

% of generation | ||

| 1 | Coal and gas | 228 | 63 | 1,072 | 80 | 282 | 36 | 1,393 | 56 |

| 2 | Hydro | 45 | 12.5 | 139 | 10.1* | 61 | 7.5 | 206 | 8 |

| 3 | Renewable | 82.5 | 22.7 | 126 | 9.2 | 455 | 54.5 | 805 | 32 |

| 4 | Nuclear | 6.7 | 1.9 | 378 | 2.7 | 19 | 2.3 | 113 | 5 |

| 362 | 1376 | 817 | 2,518 |

*Including import from Bhutan

Source: Central Electricity Authority

- India will meet 50 per cent of energy requirements from renewable: India intends to not invests in coal source

According to the CEA, in 2019, India was meeting 9.2 per cent of its electricity generation from renewables. By 2021, with an increase in renewable energy capacity to 102 GW the generation had increased to roughly 12 per cent and so, it means that we need to increase this to meet the 50 per cent electricity generation target by 2030.

India’s power requirement in 2030 is projected to be 2,518 BU and if we target to meet 50 per cent of our requirements from renewables, then the installed capacity will have to increase from the planned 450 GW to 700 GW.

If we consider hydroelectricity as part of renewables — as it is considered globally — then we will need to increase new renewable capacity to 630 GW. This is definitely achievable.

India’s target and energy plan for 2030 also implies that India will restrict its coal-based energy; currently, roughly 60 GW of coal thermal power is under construction and in the pipeline.

According to CEA, India’s coal capacity will be 266 GW by 2030 — which is an addition of 38 GW (which is roughly, what is under construction currently). This means India has stated that it will not invest in new coal beyond this.

- India will reduce projected carbon emissions by 1 billion tones (Gt) from 2021-2030: Doable, challenge the world to follow this

India’s current CO2 emissions (2021) are 2.88 Gt. According to the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE)’s projections based on the median annual rate of change in the past decade 2010-2019, India’s generation in a business-as-usual scenario will be 4.48 Gt in 2030.

According to this target, India will cut its carbon emission by 1 billion tons (1 Gt) and therefore, our emissions in 2030 will be 3.48 Gt.

This means that India has set an ambitious goal to cut its emissions by 22 per cent.

In terms of per capita: India would be 2.98 tonnes of CO2 per capita and as per this target it will be 2.31 tonnes per capita. If you compare this to the world, US will be 9.42 tonnes in 2030, EU 4.12 in 2030, UK, the CoP26 host, 2.7 in 2030 and China will be 8.88 CO2 tonnes per capita.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), global CO2 emissions must be 18.22 Gt in 2030 for the world to stay below 1.5°C rise in temperature. If we take the global population in 2030 and divide this amount, it would mean that the entire world has to be 2.14 tonnes per capita of CO2 in 2030.

India is reaching this goal and most importantly, it will do so without adding to the cumulative emissions in the atmosphere. This is where the entire world should commit to go in 2030.

In terms of the carbon budget: With the new Nationally Determined Contribution announcement (November 2, 2021), India will occupy: Nine per cent of the remaining IPCC 400 Gt carbon budget for 1.5°C by 2030; 8.4 per cent of world emissions in this decade; and 4.2 per cent of world emissions between 1870-2030.

- Carbon intensity reduction by 45 per cent: India needs to work on carbon-intense sectors

Carbon intensity measures the emissions of CO2 of different sectors of the economy and demands that these are reduced as the economy grows. According to CSE’s observations, India has achieved 25 per cent of emission intensity reduction of gross domestic product between 2005 -2016, and is on the path to achieve more than 40 per cent by 2030.

But this means that India will have to take up enhanced measures to reduce emissions from the transport sector, the energy-intensive industrial sector, especially cement, iron and steel, non-metallic minerals and chemicals.

It would also require India to reinvent its mobility systems so that we can move people, not vehicles — augment public transport in our cities and improve thermal efficiency of our housing. All that is in our best interests.

- Net Zero by 2070: It challenges the developed countries and China to be more ambitious

According to the IPCC, global emissions must halve by 2030 and reach Net Zero by 2050. Given the enormous inequity in emissions in the world, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries must then reach Net Zero by 2030, China by 2040 and India and the rest of the world by 2050.

However, the targets for Net Zero are both inequitable and unambitious. According to this, OECD countries have declared a Net Zero target for 2050 and China for 2060.

Therefore, India’s Net Zero target of 2070 is an extension of this and cannot be argued against. However, this combined Net Zero goal will not keep the world below 1.5°C temperature rise and it means that OECD countries must frontload their emission reductions by 2030.

Most importantly, China which will occupy 33 per cent of the remaining budget, must be asked to reduce its emissions drastically in this decade. China alone will add 126 Gt in this decade.

The future

India has accepted a massive transformation of our energy systems, which will be designed for the future and compliant with the new climate change goals.

The big issue that must concern us as we move ahead — and this will remain the discussion for the future — will be to ensure that growth is equitable and that the poor in the country are not denied their right to development in this new energy future.

The per capita emissions of India remain low, because we have massive numbers of people who still need energy for their development. Now, in the future, as we have set ourselves the goal to grow without pollution, we must work on the increasing clean, but affordable, energy for the poor.

As carbon dioxide emissions accumulate in the atmosphere — average residence time is 150-200 years — and it is this stock of emissions that “force” temperatures to rise, India has committed not to add to this burden.

This natural debt of the already industrialised world and China now needs to be paid for. And this is why, Prime Minister Modi is correct in saying that this requires massive transfer of funds and that these funds must be measurable. It is ironical that climate change funding remains non-transparent and without verification.