Indian industry is huge and powerful. Most environmentalists believe that it has done little to reduce pollution. Is there, therefore, anything that the civil society can do to change the situation? I am delighted to present to the readers of Down to Earth ( dte ) the results of an exercise carried out by the Centre for Science and Environment ( cse ) to rate the environmental performance of Indian companies, which we hope will go a long way in bringing about adequate public pressure on the companies as well as the regulatory and financial agencies to take better care of the environment.

Indian industry is huge and powerful. Most environmentalists believe that it has done little to reduce pollution. Is there, therefore, anything that the civil society can do to change the situation? I am delighted to present to the readers of Down to Earth ( dte ) the results of an exercise carried out by the Centre for Science and Environment ( cse ) to rate the environmental performance of Indian companies, which we hope will go a long way in bringing about adequate public pressure on the companies as well as the regulatory and financial agencies to take better care of the environment.

This exercise started nearly four-and-a-half years ago. During a visit to the United States, I had come across a magazine which had carried a feature on a non-governmental organisation ( ngo ) called the Council of Economic Priorities ( cep ) based in New York. A key activity of cep , the article said, was to rate the social and environmental performance of us companies. As several us businesspersons now want to invest only in socially-responsible and environment-friendly companies, cep 's ratings are used by financial companies handling these investments to decide which units meet these criteria.

This sounded like an interesting idea even for India where little is known about the environmental performance of industrial firms. I, therefore, asked my colleagues at cse to study the possibility of undertaking an environmental rating programme for Indian companies. A paper was prepared which showed that a large part of the funds for industrial investment come from government financial institutions instead of the stock-market unlike the us . As government agencies are duty-bound to protect the environment, whereas the stock market has no such responsibility, one would expect these agencies to be interested in the environmental ratings of the firms they invest in. Many meetings were held, which included eminent economists like Dr Raja Chelliah. All participants heartily endorsed the concept, but we still had to work out the strategy and rating methodology, all of which looked extremely daunting. It was clear that if the rating exercise meant a detailed environmental audit of each company before it was rated, then the exercise would be so monumental and time-consuming that it would become an almost impossible exercise.

A key activity of cep , the article said, was to rate the social and environmental performance of us companies. As several us businesspersons now want to invest only in socially-responsible and environment-friendly companies, cep 's ratings are used by financial companies handling these investments to decide which units meet these criteria.

This sounded like an interesting idea even for India where little is known about the environmental performance of industrial firms. I, therefore, asked my colleagues at cse to study the possibility of undertaking an environmental rating programme for Indian companies. A paper was prepared which showed that a large part of the funds for industrial investment come from government financial institutions instead of the stock-market unlike the us . As government agencies are duty-bound to protect the environment, whereas the stock market has no such responsibility, one would expect these agencies to be interested in the environmental ratings of the firms they invest in. Many meetings were held, which included eminent economists like Dr Raja Chelliah. All participants heartily endorsed the concept, but we still had to work out the strategy and rating methodology, all of which looked extremely daunting. It was clear that if the rating exercise meant a detailed environmental audit of each company before it was rated, then the exercise would be so monumental and time-consuming that it would become an almost impossible exercise.

Soon thereafter, my cancer recurred and I had to go back to the research hospital in Washington, where I had been treated earlier. On one of those days when I was out of the hospital and not feeling down and out, I decided to find out cep 's phone number and then sent a fax to the head of cep saying that I would like to see her, if possible, in New York to seek her help for setting up an environmental rating programme in India. Within a few hours, I got a return fax from an excited young man named Paul Hilton who had read my earlier writings on forestry and who would even be happy to take leave and come to India to help me set up the programme. I was really surprised. How does somebody who works with the Wall Street? Curious, I picked up the phone and spoke to Paul and it turned out that he was a young anthropologist who had once worked with an ngo in Udaipur called Astha and had read cse 's publications on Indian tribals and their relationship with their environment. I explained to Paul that we needed help from someone who could work out an rating process for us. "I will do anything to come and help," said Paul with a sense of excitement that was truly infectious. I immediately sent a message to cse in to start putting together a small team with which Paul could work on his arrival in Delhi. After my treatment ended, about six months later, Paul took leave from his organisation, at the risk of losing his job, to join us in Delhi.

But talking to Paul, we soon realised that it was not possible for us to adopt the cep strategy. cep simply uses the Toxics Releases Inventory, a database carefully maintained by the United States Environment Protection Agency ( usepa ), which has year-wise information on the wastes and emissions of companies and is openly accessible. Once this data is available, it is easy to set up benchmarks and rate accordingly. In India, the Central government does not maintain such a centralised database and even the data that it has on companies, is not easily available to the public.

Moreover, we felt that even if we went to the courts to seek access to the data available with the government and undertook a rating exercise on the basis of this data, the environmental community would simply laugh at us because there is little credibility in the data being supplied to the government. As many companies do not meet air and water standards, for which they can be prosecuted and even closed down, there is a tendency to report false data. Even if the companies report correct data, nobody believes them. This is totally contrary to the credibility enjoyed by usepa 's Toxics Releases Inventory.

This realisation totally stumped us. Undertaking an environmental rating exercise in India literally meant creating a new database on Indian companies. How were we to attempt such a massive task, especially one which was cost-effective and manageable by an ngo ? Then a thought struck us. Why don't we go to the companies themselves and ask for data on their environmental performance, get the data reviewed by technical experts and then further assessed through field visits which would include discussions with the local pollution control boards, local communities, ngo s and the media?

But why would companies be prepared to cooperate with this exercise? Our argument was simple. Let us not mix apples and oranges. In other words, let us not rate automobile companies together with paper companies. Let us rate one sector at a time. And within any sector, we felt that there would always be some firms which are making an effort and they would have an incentive to seek a public pat on their back. This itself will separate the good ones from the bad.

In order to push this 'reputational incentive' further, we decided to use the carrot and stick policy. The stick was a 'default option' under which we would automatically rate any company which does not disclose information as the worst company. The logic being that whereas a company can legitimately argue that its financial dealings are its private business, its environmental impact is a public matter simply because the environment belongs to the public. Therefore, non-disclosure of its environmental is just not acceptable. This argument is also supported by global trends. More than 1,000 companies in the West voluntarily publish an annual environmental report. So voluntary disclosure in the case of environment is today an accepted business practice. The carrot, on the other hand, we thought could be a certain weightage in the ratings given to companies who are trying to make a difference. In other words, let us begin by assuming that all Indian companies have been performing badly on the environmental front -- partly because of inadequate enforcement of Indian laws and partly because political and industrial leaders have not considered pollution control to be a serious issue. But if a company can convince us that it is making an effort to set up good environmental management policies to bring about a change in its current environmental performance, then we would respect that effort and give it a certain weightage. Over time, this weightage would be reduced and full weightage given only to actual environmental performance.

Though we had a sense that this approach would make the rating exercise feasible, we still had a nagging doubt whether it would actually work. So the Green Rating Project ( grp ) team, as it was now called, decided to meet industrial associations, senior executives of a few companies and write off letters to more than 1,250 companies asking whether they would like to participate in such an exercise. The response was excellent.

Nearly 55 companies responded expressing an interest. Though only about four per cent of the companies agreed to join the project voluntarily, the interesting fact was that most of these 55 companies were market leaders in their industrial sector.

This was very encouraging since companies which drive the market were now supporting cse to increase the environmental concern within the industrial sector. Our belief was, thus, confirmed. There will always be some who would come forward to get the benefit of the 'reputational incentive' offered by the rating process. And this was a good starting point for the rating exercise.

The discussions that the cse team had with various people also opened up a window for financial support. The staff of the United Nations Development Programme ( undp ), which was then formulating a new cycle of environmental assistance to India, found the project very exciting and offered to provide funds for it. Subsequently, the ministry of finance ordered the undp that it could not give any funds directly to ngo s and that its funds had to be routed through the substantive ministries. The ministry of environment and forests, too, gave full support to the project.

Meanwhile, in order to give high credibility to the exercise, we approached senior politicians, scientists, lawyers and judges, journalists, and members of the environmental community to support the project by participating in the Project Advisory Panel. Former finance minister, Dr Manmohan Singh, gave us his full support and graciously agreed to chair the panel. The former Union minister of environment and forests, Mr Saifuddin Soz, also agreed to join the panel together with the former Chief Justice of India, Justice P N Bhagwati, and eminent agricultural scientist Dr M S Swaminathan.

With all this in place, we decided to choose as pilot projects, those industries which would have environmental impacts at different stages of their product life cycle -- first the pulp and paper industry because of its impacts mainly at the raw material and production stages and then the automobile industry because of its impacts mainly at the product use stage.

When it came to organising actual visits to the plants we were faced with a major logistical and financial problem. India is a large country. The large companies in the pulp and paper sector alone have 31 plants spread across 13 states. If cse staff members were to visit all these plants, it would take an enormous time and effort. This is where we decided to make the rating process as participatory as possible by involving dte readers. dte readers have some extraordinary strengths. dte is neither a film magazine nor a magazine about political scams. Every single dte reader is a serious and intelligent person. Moreover, dte 's readership, though tiny by mainstream media standards, reaches out to more nooks and corners of this country than any magazine or newspaper except possibly India Today . dte today has readers all the way from Ukhrul in Manipur to Kasaragod in Kerala. Therefore, we decided to put out a notice in dte that we were setting up a Green Rating Network and invited them to join. The job involved visiting a plant within the state where the reader lived, after being properly briefed, and interviewing and collecting data from pollution control officials, local communities, ngo s and media. The work would probably take about a week or more. We would cover the travel costs but the honorarium would be a mere Rs 1,000. Over 200 people responded. We asked for their biodatas and found we had a treasure of serious and interested people here who wanted to contribute to the environmental effort. The respondents included journalists, doctors, engineers, even some pollution control officials, social workers and so on.

It was amazing that this entire effort took only one but extremely hard-working young man, Chandra Bhushan, to carry out the entire exercise. He did get the support of the full institution but for long had only interns to help him directly in his work. The three-member technical panel consisting of leading paper technologists also played a key role in assessing all the data provided by companies. During the entire process, something totally unexpected happened. The pulp and paper sector is a highly polluting sector and, therefore, has a lot to hide. But contrary to all our expectations literally every private company slowly joined the exercise. Even the two public sector companies -- Mysore Paper Mills in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu Papers Limited -- that were missing till about a fortnight before the release of the ratings decided to share information with us.

The private sector has responded with considerable openness to this entire exercise. A few months ago, as we were nearing the end of the exercise, Chandra Bhushan came to me and said that Ballarpur Industries Ltd., the largest paper company in the country, had not yet responded despite several reminders. So should we apply the 'default option' to them -- in other words, will we rate them the last because of non-disclosure? I said that as a last effort we should write to Mr L M Thapar, the head of the company. We could not believe it. Our letter to him brought an almost immediate response. Within days, the company's officials were in touch with us asking us for our questionnaire and giving us the information needed by us.

Within cse , there has always been a debate on how industry will respond to grp when cse also has campaigns against pulp and paper companies being given access to public forest lands for plantations and against automobile companies for neglecting pollution and public health implications of their vehicles. For some time, even the grp team was unsure how companies would look at the institution -- one arm of which was attacking their interests and another arm of which was going to rate them for their work? Would they see grp as an unbiased exercise and, therefore, collaborate with it or would they shy away from it?

I, too, had persistent doubts. But I must say that I am by now amazed by the response of the private sector. Let me give an example. Readers of dte are aware of the Rs 100 crore legal notice that was sent to us by telco , one of India's leading automobile companies, against an article that was written by my colleague, Sunita Narain, and me ( Down To Earth , Vol 8, No 1 and No 4). And we also have a campaign against the dieselisation of private vehicles which can seriously damage telco 's investments. Exactly at the same time when Sunita and I were telling the press that we would love to see the company in court, our colleague, Chandra Bhushan, was getting in touch with automobile companies, including telco , to start the rating process for this sector. telco officials had a year or so ago expressed an interest in participating in the exercise. But now they were telling Chandra Bhushan that given the current tensions between cse and telco this would be quite difficult.

Chandra Bhushan was unhappy but it was not to be for long. At the height of our campaign against diesel vehicles, we got a letter from Mr V M Raval, executive director, automobile business unit, saying that his company would be happy to join the rating exercise. And added, "We welcome the initiative taken by your organisation and confirm that we would join your green rating programme for the automobile industry. We would provide you with whatever information that may be required to the best of our ability and support you in your endeavour to improve the environmental performance of the industry, and the nation as a whole." We could not believe it. This was truly a surprise. And a very pleasant one.

If the GRP has convinced me of anything, once again, it is that India's biggest strength is its democracy. It gives its people the chance to organise themselves, protest, push, create and change. Economic liberalisation and privatisation need not do any environmental damage if adequate space and support is given to the civil society to act as a powerful and knowledgeable watchdog. This is what democracy is all about: checks and balances.If the GRP has convinced me of anything, once again, it is that India's biggest strength is its democracy. It gives its people the chance to organise themselves, protest, push, create and change. Economic liberalisation and privatisation need not do any environmental damage if adequate space and support is given to the civil society to act as a powerful and knowledgeable watchdog. This is what democracy is all about: checks and balances.

If grp continues, I am convinced it will not only help to improve environmental governance in the country by introducing transparency into the environmental performance of Indian companies and put public pressure on them to constantly upgrade their work in this area but it will also go a long way in lifting the environmental concern within the companies themselves right to the top. grp will make industrial leaders realise that environmental compliance should not be restricted to meeting government norms but can actually become a proactive exercise in which official norms constitute only the minimum effort.

Our experience in rating the pulp and paper sector has shown that many firms have found it an extremely useful educational exercise. "We happily welcome the public announcement to be made by cse on the paper industry's environmental record," said Suresh Kilam, chief executive officer, Sinar Mas-India.

This is not new. Paul had also told us that even in the us , cep 's rating scheme had both helped raise environmental concern to the top-level management where the most vital decisions are taken and helped to get a better picture of what is expected from it in terms of environmental management.

In a country like India, it is in the industry's own interest to take a proactive role in environmental management. India is just beginning to industrialise, urbanise and motorise and yet it is already heavily polluted. We will see incredible levels of pollution in the years to come unless serious efforts are made to prevent it (see Down to Earth , Vol 7, No 17). If pollution grows, there will be public protests, given the space Indian democracy provides, and either the politicians or the courts will have to respond. In such a situation, it is industrialists who are likely to find their investments most threatened. Judicial activism, community and ngo protests are already beginning to bite. And, therefore, in a sense, industrial leaders' eagerness to cooperate with grp should not be surprising. But the expression of that eagerness in the form of voluntary participation in grp has pleasantly surprised us.

The following pages present some of our key findings on the environmental performance of the country's pulp and paper industry. We hope our readers will share our excitement with this project.

-- Anil Agarwal

For assessing actual environmental performance, cse decided to use the broader Life Cycle Analysis ( lca ) approach instead of the more restricted Environmental Impact Assessment ( eia ) approach used by the government to clear projects. The eia approach only assesses environmental impacts at the production site whereas the lca approach assesses the full environmental impact of a product, which is also called the 'cradle-to-grave' analysis. It includes the environmental impact of the raw materials obtained for making a product (the impact on forests, for instance, for obtaining wood to make paper), the environmental impact at the production stage (chemicals, for instance, that is used in the pulp-bleaching stage) and then the environmental impacts at the time the product is being used and is being disposed off (whether the company recycles wastepaper). A combination of all these factors gives the rating a more holistic image, in tune with the ground reality. Thus, the rating of the actual environmental performance is comprehensive (See diagram: Cradle-to-grave ).

For assessing actual environmental performance, cse decided to use the broader Life Cycle Analysis ( lca ) approach instead of the more restricted Environmental Impact Assessment ( eia ) approach used by the government to clear projects. The eia approach only assesses environmental impacts at the production site whereas the lca approach assesses the full environmental impact of a product, which is also called the 'cradle-to-grave' analysis. It includes the environmental impact of the raw materials obtained for making a product (the impact on forests, for instance, for obtaining wood to make paper), the environmental impact at the production stage (chemicals, for instance, that is used in the pulp-bleaching stage) and then the environmental impacts at the time the product is being used and is being disposed off (whether the company recycles wastepaper). A combination of all these factors gives the rating a more holistic image, in tune with the ground reality. Thus, the rating of the actual environmental performance is comprehensive (See diagram: Cradle-to-grave ). A competent technical panel is vital for the Green Rating Project. Keeping this in mind, cse selected three leading technologists in the pulp and paper sector to form the Technical Consultants Panel ( tcp ) to help in the rating the industry. The tcp members are:

A competent technical panel is vital for the Green Rating Project. Keeping this in mind, cse selected three leading technologists in the pulp and paper sector to form the Technical Consultants Panel ( tcp ) to help in the rating the industry. The tcp members are: June-July 1997: The first letter sent to the 28 companies in the pulp and paper sector requesting them to send their annual reports and brief profile. By the end of August 1997, only seven got back to cse with their annual report and only one of them, the West Coast Paper Mills Ltd ( wcpml ), Karnataka, sent its profile.

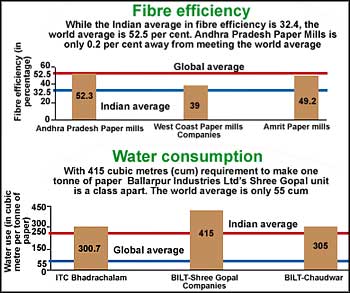

June-July 1997: The first letter sent to the 28 companies in the pulp and paper sector requesting them to send their annual reports and brief profile. By the end of August 1997, only seven got back to cse with their annual report and only one of them, the West Coast Paper Mills Ltd ( wcpml ), Karnataka, sent its profile. With a score of 42.75 per cent, J K Paper Mills takes the lead in environmental performance, followed by Andhra Pradesh Paper Mills Ltd with 38.50 per cent. Both these mills have been given three leaves rating. The best company would have received five leaves rating, but sadly no one deserved it. At least, not yet. Mukerian Paper Mills and Amrit Paper Mills are the tailenders but with a neck and neck race between the poor performers.

|

COMPANY |

SCORE |

RANK |

RATING |

|

J K Paper Mills, Orissa |

42.75 |

1 |

|

|

Andhra Pradesh Paper Mills Ltd, Andhra Pradesh |

38.50 |

2 |

|

|

Sinar Mas Pulp & Paper (India) Ltd, Maharashtra |

37.40 |

# |

|

|

BILT-Ballarpur Unit, Maharashtra |

33.44 |

3 |

|

|

Hindustan Newsprint Ltd, Kerala |

33.30 |

4 |

|

|

South India Viscose Industries Ltd, Tamil Nadu |

31.73 |

5 |

|

|

Pudumjee Pulp & Paper Mills Ltd, Maharashtra |

31.44 |

6 |

|

|

Tamil Nadu Newsprint & Papers Ltd, Tamil Nadu |

31.40 |

7 |

|

|

ITC-Bhadrachalam Paperboards Ltd, Andhra Pradesh |

31.15 |

8 |

|

|

Century Pulp & Paper, Uttar Pradesh |

31.07 |

9 |

|

|

Nagaon Paper Mills, Assam |

28.70 |

10 |

|

|

Seshasayee Paper & Boards Ltd, Tamil Nadu |

28.20 |

11 |

|

|

West Coast Paper Mills Ltd, Karnataka |

27.67 |

12 |

|

|

BILT-Asthi Unit, Maharashtra |

27.10 |

13 |

|

|

BILT-Yamunanagar Unit, Haryana |

25.70 |

14 |

|

|

Central Pulp Mills Ltd, Gujarat |

25.35 |

15 |

|

|

Star Paper Mills Ltd, Uttar Pradesh |

24.76 |

16 |

|

|

Shree Vindhya Paper Mills Ltd, Maharashtra |

24.70 |

17 |

|

|

BILT-Sewa Unit, Orissa |

23.75 |

18 |

|

|

Orient Paper Mills, Madhya Pradesh |

22.10 |

19 |

|

|

Mysore Paper Mills Ltd, Karnataka |

21.60 |

20 |

|

|

Cachar Paper Mills, Assam |

21.43 |

21 |

|

|

Rama Newsprint & Papers Ltd, Gujarat |

21.10 |

22 |

|

|

BILT-Chaudwar Unit, Orissa |

21.06 |

23 |

|

|

Nath Pulp & Paper Mills Ltd, Maharashtra |

20.80 |

24 |

|

|

Grasim Industries Ltd (Mavoor), Kerala |

20.65 |

25 |

|

|

Mukerian Papers, Punjab |

20.01 |

26 |

|

|

Amrit Paper, Punjab |

19.01 |

27 |

# Sinar Mas is not rated as it is a new company and its data does not match with the period taken for the Green Rating Project. Three other mills — Sirpur Paper

Mills, Orient Paper Mills-Brajrajnagar and Nagaland Pulp and Papers — were not in operation during the data collection phase of the Green Rating Project period

• Environment policy/policy statement: Even if these companies do not have environment policy statements with all the details worked out, they do have formal environment policy statements. They also have environment departments with senior managers looking after their day-to-day affairs

• Environment policy/policy statement: Even if these companies do not have environment policy statements with all the details worked out, they do have formal environment policy statements. They also have environment departments with senior managers looking after their day-to-day affairs It is no surprise that the only Indian company that had an iso 14001 certificate even before the Green Ratings Project began has come out on top. But even the top-rated company has only scored 42.75 per cent.

It is no surprise that the only Indian company that had an iso 14001 certificate even before the Green Ratings Project began has come out on top. But even the top-rated company has only scored 42.75 per cent.| PARAMETERS | WEIGHTED SCORE | WEIGHTED TOTAL |

| Corporate policy and management system | 18.5 | 35 |

| Input management | 1.37 | 8 |

| Process management | 7.06 | 21 |

| Recycling and reuse | 4.6 | 10 |

| Waste management and pollution controle | 1.29 | 10 |

| Compliance and community perception | 6.75 | 10 |

| Total | 40.19 | 94 |

The company that has been rated second is located on the left bank of river Godavari in the pilgrim town of Rajahmundry, East Godavari district, Andhra Pradesh. Not that Andhra Pradesh Paper Mills Ltd's ( appml 's) environmental performance is extraordinary. But it shows consistency. The mill is ranked above average in several departments. appml has also been regularly making profits.

The company that has been rated second is located on the left bank of river Godavari in the pilgrim town of Rajahmundry, East Godavari district, Andhra Pradesh. Not that Andhra Pradesh Paper Mills Ltd's ( appml 's) environmental performance is extraordinary. But it shows consistency. The mill is ranked above average in several departments. appml has also been regularly making profits.| PARAMETERS | WEIGHTED SCORE | WEIGHTED TOTAL |

| Corporate policy and management system | 10.75 | 35 |

| Input management | 3.42 | 8 |

| Process management | 7.47 | 21 |

| Recycling and reuse | 6.10 | 10 |

| Waste management and pollution controle | 2.14 | 10 |

| Compliance and community perception | 8.21 | 15 |

| Total | 38.10 | 99 |

Two Leaves Company

Two Leaves Company | PARAMETERS | WEIGHTED SCORE | WEIGHTED TOTAL |

| Corporate policy and management system | 10.75 | 35 |

| Input management | 0.69 | 8 |

| Process management | 10.04 | 21 |

| Recycling and reuse | 4.9 | 10 |

| Waste management and pollution controle | 1.56 | 10 |

| Compliance and community perception | 4.5 | 14.5 |

| Total | 32.73 | 98.5 |

• Lack of environment policy/policy statement: Let alone having a comprehensive environmental policy statement, most of these companies do not even have a general environment policy statement. They have not made any effort to set up an environment department

• Lack of environment policy/policy statement: Let alone having a comprehensive environmental policy statement, most of these companies do not even have a general environment policy statement. They have not made any effort to set up an environment department Grasim Industries Ltd has a plant along the river Chaliyar at Mavoor, district Kozhikode, Kerala. It produces rayon-grade pulp and is entirely based on bamboo and wood for raw materials. The mill claims that it has an environmental policy statement, though no document has been provided to substantiate the same. The fact that the mill is not aware of the details of the policy raises the possiblity that there is no policy or if it is there, it is for namesake.

Grasim Industries Ltd has a plant along the river Chaliyar at Mavoor, district Kozhikode, Kerala. It produces rayon-grade pulp and is entirely based on bamboo and wood for raw materials. The mill claims that it has an environmental policy statement, though no document has been provided to substantiate the same. The fact that the mill is not aware of the details of the policy raises the possiblity that there is no policy or if it is there, it is for namesake.| PARAMETERS | WEIGHTED SCORE | WEIGHTED TOTAL |

| Corporate policy and management system | 4.05 | 35 |

| Input management | 2.26 | 8 |

| Process management | 7.07 | 21 |

| Recycling and reuse | 4.50 | 10 |

| Waste management and pollution controle | 2.36 | 9 |

| Compliance and community perception | 0 | 15 |

| Total | 20.24 | 98 |

As the name suggests, Mukerian Papers Ltd ( mpl ) has its plant at Mukerian, about 40 km from Pathankot in Punjab. Although mpl has been making profits in the past, its turnover and profitability have declined continuously since 1996-97.

As the name suggests, Mukerian Papers Ltd ( mpl ) has its plant at Mukerian, about 40 km from Pathankot in Punjab. Although mpl has been making profits in the past, its turnover and profitability have declined continuously since 1996-97.| PARAMETERS | WEIGHTED SCORE | WEIGHTED TOTAL |

| Corporate policy and management system | 5.52 | 35 |

| Input management | 4.48 | 8 |

| Process management | 8.54 | 21 |

| Recycling and reuse | 0 | 10 |

| Waste management and pollution controle | 1.29 | 8 |

| Compliance and community perception | 0 | 15 |

| Total | 19.46 | 97 |

Amrit Paper Mills ( apm ) has a plant at Saila Khurd in Hoshiarpur district, Punjab. Though the company claims to have an environmental policy, it seems doubtful as no documented proof of the policy has been provided. The company also claims to have environment departments both at the corporate level and the unit level. But as per the feedback of the cse surveyor, it seems that the company does not have an environment department.

Amrit Paper Mills ( apm ) has a plant at Saila Khurd in Hoshiarpur district, Punjab. Though the company claims to have an environmental policy, it seems doubtful as no documented proof of the policy has been provided. The company also claims to have environment departments both at the corporate level and the unit level. But as per the feedback of the cse surveyor, it seems that the company does not have an environment department. | PARAMETERS | WEIGHTED SCORE | WEIGHTED TOTAL |

| Corporate policy and management system | 5.15 | 35 |

| Input management | 2.36 | 8 |

| Process management | 4.72 | 21 |

| Recycling and reuse | 0.05 | 8 |

| Waste management and pollution controle | 2.92 | 7 |

| Compliance and community perception | 1.75 | 12.50 |

| Total | 17.40 | 91.50 |

Mind your business

Mind your business Company that had an environment policy before GRP started

Company that had an environment policy before GRP started  T he pulp and paper industry is one of the oldest industries in India: the first paper mill was set up as early as 1832 at Serampore in Hooghly district of West Bengal. But in terms of production capacity, the industry remains very small. The mills have an aggregate capacity of 3.8 million tonnes per annum (tpa). But the effective capacity is only 2.6 million tpa, because many of these mills are sick. In the newsprint segment, the total capacity is around 0.45 million tpa, of which 73 per cent is dominated by four major public sector mills, while the rest is shared by 14 small players.

T he pulp and paper industry is one of the oldest industries in India: the first paper mill was set up as early as 1832 at Serampore in Hooghly district of West Bengal. But in terms of production capacity, the industry remains very small. The mills have an aggregate capacity of 3.8 million tonnes per annum (tpa). But the effective capacity is only 2.6 million tpa, because many of these mills are sick. In the newsprint segment, the total capacity is around 0.45 million tpa, of which 73 per cent is dominated by four major public sector mills, while the rest is shared by 14 small players. Many recent pollution prevention efforts in the pulp and paper industry have focused on getting rid of the use of chlorine for bleaching, a process which helps to increase the brightness of the paper. Elemental chlorine (that is, pure chlorine) or chlorine dioxide is generally used for bleaching but, in the process, large amounts of chlorinated pollutants such as dioxins -- a persistent organic pollutant with very high cancer-causing potential -- are released into the water. Hence, there is an increasing trend worldwide to reduce the use of both elemental chlorine and chemicals containing chlorine.

Many recent pollution prevention efforts in the pulp and paper industry have focused on getting rid of the use of chlorine for bleaching, a process which helps to increase the brightness of the paper. Elemental chlorine (that is, pure chlorine) or chlorine dioxide is generally used for bleaching but, in the process, large amounts of chlorinated pollutants such as dioxins -- a persistent organic pollutant with very high cancer-causing potential -- are released into the water. Hence, there is an increasing trend worldwide to reduce the use of both elemental chlorine and chemicals containing chlorine.  The pulp and paper sector must steadily move towards sustainable industrial development. Here are some actions which could help:

The pulp and paper sector must steadily move towards sustainable industrial development. Here are some actions which could help:  J K Paper Mills ( jkpm ) of Raygada in Orissa has been rated the greenest paper mill in India. jkpm is followed by Andhra Pradesh Paper Mills Ltd ( appml ) and the Ballarpur unit of Ballarpur Industries Ltd. The significant feature of jkpm is a modern pulping process called rapid displacement heating ( rdh ), which consumes less energy and its fibre efficiency is also high. The amount of bleaching chemicals and water required is smaller. jkpm consumes only about 12 kg of elemental chlorine per tonne of paper produced as compared to most other mills which consume about 100 kg.

J K Paper Mills ( jkpm ) of Raygada in Orissa has been rated the greenest paper mill in India. jkpm is followed by Andhra Pradesh Paper Mills Ltd ( appml ) and the Ballarpur unit of Ballarpur Industries Ltd. The significant feature of jkpm is a modern pulping process called rapid displacement heating ( rdh ), which consumes less energy and its fibre efficiency is also high. The amount of bleaching chemicals and water required is smaller. jkpm consumes only about 12 kg of elemental chlorine per tonne of paper produced as compared to most other mills which consume about 100 kg.