Big companies dominate cement. Grasim Industries Limited (gil), owned by the Aditya Birla Group, is the largest cement manufacturer in the country and the eighth largest in the world. Associated Cement Companies Limited (acc) is second: it was controlled by the Tatas before Ambuja Cements India Ltd, a joint venture between the Ambuja Group and the Swiss multinational Holcim, bought into it. Gujarat Ambuja Cement Limited (gacl), held by the Ambuja Group, south India-based India Cement and BK Birla's Century Textiles and Industries Ltd follow in that order. The top five collectively control 52 per cent of the market.

The big companies are, in fact, growing bigger and more profitable. The gross profit margin of the top five in the last five years was as good as those of the top five global companies -- more than 20 per cent of turnover. gacl is one of the most profitable cement companies in the world, with a great profit-turnover ratio. Several factors have contributed to this scenario. It gets cheap raw material in the first place and cuts costs by using waste materials -- like flyash. With raw material costs pegged at just 7.3 per cent of turnover, Indian cement is on velvet.

Most cement companies modernised after 1989 -- installing state-of-the-art automation. The result is that their major cost, energy, which accounts for 25 per cent of turnover, compares favourably with the best in the world. Automation has reduced labour costs by 3.4 per cent of turnover.

The industry is so cost-efficient that few multinationals can compete without availing the advantages entailed by a base in the country. So global players have been buying into Indian companies. France-based Lafarge Cements, the Holcim group and Italcementi from Italy have entered markets by investing in or buying out Indian companies. Holcim invested in Kalyanpur Cements in 1990; Lafarge acquired Tata Steel's plants in 1999; and Italcementi set up shop with the K K Birla group, acquiring a 50 per cent stake in Zuari Cement in 2000.

Sunshine or downpour, there is something rotten in the state of India's cement industry. When the Centre of Science and Environment's (cse's) green rating project (grp) did a job on 41 plants owned by 23 companies, with a 79 per cent of total installed capacity and 83 per cent production, it found the downside of this massive boom: an immensely destructive ecological cost spiralling out of control. What follows is grp's comprehensive audit.

Click here to see the Report Card>>

Limestone, the main raw material in cement manufacturing, is obtained by large-scale open cast mining. In India, this stage of the cement life-cycle is the industry's weakest link -- environmentally and otherwise. It brings conflicting interests to a head -- on the one hand, the need to extract minerals for growing economies and, on the other, the need to conserve livelihoods of local communities dependent on local resources. The absence of tight regulation and clear policy directives gives the industry an upper hand; local communities suffer because their natural resource base is degraded.

Limestone, the main raw material in cement manufacturing, is obtained by large-scale open cast mining. In India, this stage of the cement life-cycle is the industry's weakest link -- environmentally and otherwise. It brings conflicting interests to a head -- on the one hand, the need to extract minerals for growing economies and, on the other, the need to conserve livelihoods of local communities dependent on local resources. The absence of tight regulation and clear policy directives gives the industry an upper hand; local communities suffer because their natural resource base is degraded.

One reason for the massive ecological impact of mining is the fact that it changes -- often irreversibly -- the land-use patterns of an entire region. In developing countries, mining changes both landscapes and lifestyles. Most mines are located on what used to be agricultural land: almost 60 per cent of land leased by the large-scale plants is suitable for agriculture.

Taking agricultural land away for mining impacts on local economies hugely, causing alienation from the environment and loss of livelihoods. Rehabilitation packages are usually inadequate, which makes matters worse. In Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh, where the cement industry has grown rapidly, agricultural communities have had to move away from traditional lifestyles. Ecologically, the impact has been disastrous, with land being converted into quarries, thereby losing its fertility over the long haul.

Moreover, in India, much of what is designated wasteland is actually used by local communities for a variety of activities -- like grazing cattle. Thirty-seven per cent of the area taken for mining in the grp sample was earlier being used for grazing or marginal farming. The maximum impact has been in Rajasthan, which has a large population dependent on livestock, and where 88 per cent of land leased out to the cement industry falls under this category.

For the cement industry, land-use patterns, and ecological and social factors are not siting criteria, economic logic is. Forty-five per cent of plants are located in ecological sensitive areas such as hilly terrain, or near forests and wildlife sanctuaries and within coastal regulation zones.

In the early 1980s, rampant limestone mining in the Dehradun valley in Uttaranchal (then Uttar Pradesh) sparked off huge protests. It was pointed out that one of the most important functions of the limestone deposits was conservating rainwater. Decades of mining disturbed the hydrological balance of the region. In 1986, the Supreme Court banned limestone mining in the valley. All that happened was that mining shifted to Himachal Pradesh. The state has welcomed cement manufacturers, assuring local communities that jobs will be created, but the technology is a problem.

Mining technology depends on factors such as hardness and compactness of deposits and economics. In India, 88.7 per cent of limestone in the past five years was extracted by blasting. Surface miners were used to mine just 8.5 per cent of the deposits. Just four plants use surface miners -- gacl -Gujarat unit, Madras Cement Ltd- Alathiyur Works, Sanghi Cement and Gujarat Cement Works of the Ultratech group.

Using surface miners eliminates the problems commonly associated with blasting -- including noise pollution and damage to houses in the vicinity. Currently available surface miners can only be used on soft deposits (having a compressive strength less than 600 kg/cm 2). But some plants continue to use blasting to mine soft limestone -- for instance, Jamul Cement Works of the acc group, Saurashtra Cement and Lafarge India's Sonadih unit. Gujarat Sidhee Cement Limited (gscl) got a surface miner only in 2004, though its plant has been onstream since 1987. This happens because there is no regulatory pressure on the industry to switch to eco-friendly technology. Industry prefers blasting because it costs Rs 36 per tonne of material extracted, while surface mining costs Rs 47 per tonne.

When mining strikes the natural water table, the availability of water in the surrounding areas decreases. For example, in New Surjana village near the Chanderia mines of Birla Chittor, where the groundwater table has been breached, residents claim the water table had dipped from 25 feet to 400-500 feet, and wells and tube-wells have dried up.

Currently, there are no regulations to prevent breaching. Fourteen plants 39 per cent of those rated by grp have breached the groundwater table. Experts say breaching of the water table is no problem. But the fact is groundwater management is key to the future of India's ecology. Regular monitoring of groundwater levels within lease areas should be essential for mining. Currently, only 10 units monitor groundwater levels. Industry will have to accept that breaching the water table and creating the illusion that making pits are efforts at rainwater harvesting are not acceptable strategies. Proper measures have to be taken to manage groundwater properly -- through hydrological studies, by identifying and recharging natural aquifers, and creating infrastructure for water supply to nearby villages.

Mining subsidises the cement industry -- mine management is pathetic because little effort or resources are spent on it or on reclamation (see box: Subsided by mining). Less than half of the big cement plants have no reclamation programmes. The lack of credible regulation allows the industry to get away with this.

Programmes for topsoil and overburden (waste by-products) management, afforestation, rainwater harvesting or reducing siltation and runoff are at best half-hearted and most often ineffectual. Take topsoil management. Though valuable ecologically, it has no immediate economic value. Predictably, it is poorly managed. Though more than half of the topsoil excavated is supposedly stored for future reclamation efforts, only 8.7 per cent of plants have planted vegetation on topsoil dumps to reduce runoff and 35 per cent have constructed good bunds or culverts around them. Afforestation has also been neglected. Mine lease areas are, however, barren.

Reclamation doesn't really happen. Whatever reclamation happens is skewed. Most plants are going to reclaim parts of exhausted land -- 77 per cent -- by creating reservoirs. Plantations will take up just 22.6 per cent. There are no reclama-tion plans for agriculture. The perspective is bleak.

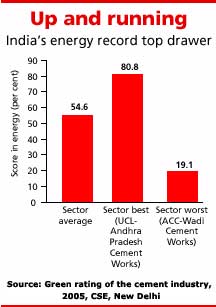

Making cement is energy-intensive. Energy accounts for a significant portion of the cost of producing cement. Most technological advancement, unsurprisingly, has been directed towards reducing its consumption. Unlike other industries in India, in which technological levels lag behind the best in the world, the cement industry is state of the art. This is the key to the Indian cement sector's competitiveness. It also makes this sector one of the most energy-efficient

(see graph: Energy drive).

Making cement is energy-intensive. Energy accounts for a significant portion of the cost of producing cement. Most technological advancement, unsurprisingly, has been directed towards reducing its consumption. Unlike other industries in India, in which technological levels lag behind the best in the world, the cement industry is state of the art. This is the key to the Indian cement sector's competitiveness. It also makes this sector one of the most energy-efficient

(see graph: Energy drive). The cement sector has another big potential -- it can solve our waste-disposal problems. The (the heart of the cement plant) acts as a scavenger, incinerating materials ranging from municipal waste to tyres. It can also use other waste -- flyash from thermal power plants, blast furnace slag from iron and steel plants, phosphogypsum from the fertiliser industry, lime sludge from the pulp and paper sector and mill scale from the iron industry. Globally, the cement industry has been an efficient waste manager -- the Indian cement industry has tried to keep in touch (see graph: Super scavenger). But there is great variation across the industry -- dictated principally by costs incurred due to location and, therefore, transportation. A Lafarge plant uses as much as 47 per cent waste as percentage of cement produced, while Sanghi Cements and Aditya Cements hardly use any.

The cement sector has another big potential -- it can solve our waste-disposal problems. The (the heart of the cement plant) acts as a scavenger, incinerating materials ranging from municipal waste to tyres. It can also use other waste -- flyash from thermal power plants, blast furnace slag from iron and steel plants, phosphogypsum from the fertiliser industry, lime sludge from the pulp and paper sector and mill scale from the iron industry. Globally, the cement industry has been an efficient waste manager -- the Indian cement industry has tried to keep in touch (see graph: Super scavenger). But there is great variation across the industry -- dictated principally by costs incurred due to location and, therefore, transportation. A Lafarge plant uses as much as 47 per cent waste as percentage of cement produced, while Sanghi Cements and Aditya Cements hardly use any. With an overall score of 36 per cent, the Indian cement industry gets a three leaves award -- an above average environment performance. Companies were rated on more than 150 performance indicators -- from assessing the environmental impact of raw material sourcing, through assessing the environmental performance of the product to assessing their initiatives in corporate environment and occupational health management. Due cognisance was also given to the perception of people involved, including communities near mines and factories. The Indian cement industry scored better than the three earlier rated by grp (see table: Discomfort zone).

With an overall score of 36 per cent, the Indian cement industry gets a three leaves award -- an above average environment performance. Companies were rated on more than 150 performance indicators -- from assessing the environmental impact of raw material sourcing, through assessing the environmental performance of the product to assessing their initiatives in corporate environment and occupational health management. Due cognisance was also given to the perception of people involved, including communities near mines and factories. The Indian cement industry scored better than the three earlier rated by grp (see table: Discomfort zone).

|

||||||||||||||||

More than 30 per cent separates the best and worst in the Indian cement industry. Moreover, no company has done well in all areas. Madras Cement Limited's Alathiyur Works has performed well in all respects, except mine management. It produces 86 per cent blended cement, uses paper bags to pack cement, surface mining technology, is energy-efficient and has done exceptionally well in reducing air pollution. It is also the only plant that has the infrastructure to handle and store raw materials.

Gujarat Ambuja's Gujarat unit, with a 48 per cent score is the second best company in the country. It uses surface miners and has a robust vision for mine reclamation and has already converted part of its exhausted mine areas into grazing land. The company has taken significant initiatives to generate livelihood opportunities by constructing rainwater-harvesting structures and outsourcing its limestone-transportation operations. The result is a top score in stakeholder perception. It has done reasonably well in energy use and emissions, but scores poorly in waste material utilisation and storage.

Three companies -- acc 's Gagal Unit in Himachal Pradesh, Prism Cement in Madhya Pradesh and JK's Laxmi Cement in Rajasthan -- with 46 per cent each, occupy the third position. Though Gagal has done everything well -- from closed storage for most raw materials to state-of-the-art pollution control technology and mine management -- the very fact that it is located in eco-sensitive Himanchal Pradesh ensures adverse environmental impact. Prism Cement has the most advanced production and pollution control technology , but its raw material handling is poor and mine management average. JK's Laxmi Cement has reached the third position by being consistent in every aspect, not exceptional in some.

The plants that are at the bottom of the heap -- India Cements Limited (Vishnupuram and Shankarnagar plant), Century Textiles' Maihar Cements at Satna, Diamond Cements at Damoh and JK Synthetic's Nimbahera plant -- are the ones which had everything to hide. Though they refused to participate, grp's research shows bad performance.

Take India Cements Limited. It is the third largest cement producer, with a 9 million-tonne capacity spread over seven plants in south India. It has expanded fast, but done little to manage pollution. The survey of its Vishnupuram plant shows fugitive emissions cause big problems.

Many plants that participated in the ratings were poor performers. But they were transparent and open enough to participate in the exercise and learn from the process. Andhra Cement told grp that they were participating not for the rating, but to develop a plan for the future.

Considering the potential for environmental destruction inherent in the industry, grp's, initial perception was that this sector was going to be one of the worst. This was right in some senses and wrong in others.

Though the cement industry remains environmentally destructive, many companies have taken measures to reduce the impact. Performance in mining remains very poor, yet it had done lots to ensure that energy consumption, co2 emissions and stack emissions remain as low as possible. In terms of production technology, it is perhaps the only industry that is sometimes global leaders. The study of the cement industry shows it is possible to align economic and environmental interests, if a reasonable regulatory framework is in place.

But it is not just a question of the physical environment. To optimise performance, the cement industry has to look at social issues, especially the question of equity. With increasing awareness and changing state policy, it is difficult to push through any project that causes deprivation without compensation. This is a problem for cement companies because their capacity to generate employment is limited. They will have to innovate, create partnerships and involve themselves in local development projects to be acceptable to people in the areas where they plan to set up shop.

Click here to see the Report Card>>

Chandra Bhushan, Monali Zeya Hazra, Radhika Krishnan, Nivit Kumar Yadav and Sujit Kumar Singh

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||