Dam safety in Himachal Pradesh be damned

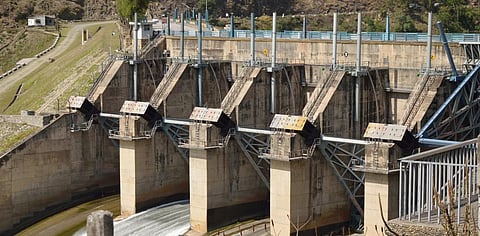

On May 3rd, 2019, Divya Himachal, a Hindi daily, reported that the 100 MW Sainj Hydropower Project in Himachal Pradesh’s Kullu district had stopped its operations after severe leakage due to massive cracks in the dam was noticed.

Owned by the Himachal Pradesh Power Corporation Ltd (HPPCL), the project has been non-operational for more than a month, creating a loss of Rs 5 crore so far for the company. However, what is shocking about the case is that the leakage has been continuing since the last two months but not a single remedial measure was taken. The project, reported Divya Himachal, is apparently moving towards a massive disaster, putting the lives of hundreds of people at risk.

This is not a one-off incident. Rather, such hazards have become synonymous with hydropower projects in the state. In the last seven years, 16 cases of accidents due to negligence have been recorded which have caused immense damage to life and property.

Yet, Himachal Pradesh, known for its booming hydro power sector, has failed to provide for monitoring and accountability mechanisms, thereby creating risks for the people. Moreover, the manner in which increasing disasters around ‘dammed’ areas are being dealt with in the state, one doubts whether dam safety cells even exist. Concrete reasons for the same were revealed in Right to Information (RTI) responses received from the Directorate of Energy (DOE).

Himachal’s mountainous landscape, though exquisite, is seismically fragile. According to Landslide Hazard Zonation Atlas of India, 2003, more than 97 per cent of the total geographical area of the state is prone to landslides.

In this highly landslide-prone state, 153 hydropower projects (HPPs) have been commissioned as of March 2019, records the DOE. Astoundingly, a 2015 study of the State Disaster Management Authority warns that 56 per cent of Himachal’s total constructed HPPs are under serious threat of landslide hazard risks. Any construction that involves underground disturbance, working near fast flowing rivers prone to flash floods and eroding the soil of steep slopes is risky business.

Despite this state of affairs, Himachal’s valleys are set to see 863 more HPPs, which are either under construction or at different stages of clearance. In hindsight, increasing the number of dams seems to be an invitation to more negligence in HPPs.

An absentee state-level dam safety cell

Currently, dam safety, which includes a series of guidelines laid out by the Central Water Commission (CWC), is the responsibility of the dam safety cells which are to be formed at both, the state and individual project proponents’ (IPPs) level.

Himachal, which had its hydropower policy laid out way back in 2006, does not pay much heed to the safety assurance of operational, under-construction or to be constructed projects. However, owing to repeated instances of negligence at various project sites, the Ministry of Multi-Purpose Projects and Power, via a notification on February 10, 2014, mandated the formation of a state-level dam safety cell.

According to the notification, the cell was to ensure safety, quality control, management of water flows, and monitor and ensure the health of hydro projects which are under implementation in all the five river basins in Himachal Pradesh.

Ideally, the cell should have been playing a role in the planning of projects and even more importantly, safety monitoring and accountability in under-construction and operational projects.

On April 14, 2019, Amar Ujala, a national Hindi daily, reported leakage in a tunnel of the Parbati Stage-III (520 MW) HPP in Sainj Valley, Himachal Pradesh, where the inhabitants of the nearby Bihali and Sampagani villages feared that the tunnel would burst open and cause complete erosion. In 2017, Parbati Stage-II HPP (800 MW), just upstream of Stage-III, met a similar fate when leakage from its tunnel impacted over a dozen villages in the Kullu district putting at risk the lives of around 400 families. In the absence of regular monitoring, our safety vis-à-vis dam safety seems fragile.

As far as collective discussion of safety issues in hydropower projects is concerned, members of the state-level dam safety cell have not even met once following their first meeting, owing to a lack of funds (based on telephonic conversation with a senior official at DOE).

Using RTI, when we asked for minutes of meetings of the cell between 2014 and 2018, those of the National Committee on Dam Safety (NCDS) were made available. Among the participants of these meetings, engineers representing the dam safety cell from Himachal made the list only in the years 2014, 2015 and 2016 whereas for 2017, the DOE’s chief engineer attended the meeting and no representative from the state marked his/her presence in 2018. This clearly reveals that the state-level dam safety cell has never held a second meeting of its own since its inception and in all probability, does not even exist now.

Missing dam safety cell at IPP level

Another instance that revealed the callous attitude of the administration was during the last monsoon when Pangi, a village in Kinnaur district, suffered loss of vegetation, forest land and trees of Deodar and Chilgoza, a near-threatened species.

All this happened when water from the flushing tunnel of the Kashang (Stage-I) HPP was suddenly released without prior warning being given to the residents. When we sought the enquiry report of the accident from the DOE under the RTI Act, our application was transferred to the HPPCL (the project proponent), with the statement that the report “is not made available to this office” and that the issue “pertains to HPPCL”.

Further, following the assessment of damages by the forest department in the same case, aggregating to a colossal Rs 17 crore, it was the office of the Deputy Commissioner and not the dam safety cell which wrote a letter to HPPCL, to “look in the matter and take further appropriate necessary action in the matter, please.” Against such a grave loss of public resources, a toothless letter of request, raising no questions about the cause of the incident shows a total absence of accountability and punitive action.

In 2014, the Ministry of Multi-Purpose Projects and Power issued a issued a letter to all IPPs and government organisations (managing dams/barrages in various river basins) of Himachal Pradesh, mandating the formation of a safety cell by each IPP for “preventive methods of minimising loss to life and property”.

But when an enquiry was conducted in the Kashang case, HPPCL formed an enquiry team consisting of engineers from the Shongtong Karcham HPP (another project of HPPCL) on an ad-hoc basis. This makes it appear like HPPCL became the sole investigator of its own crime.

The absence of safety cells at IPP level is also echoed in the CAG report of 2017 on Social, General and Economic Sectors, which highlights non-compliance by three dam authorities: Bhakra Nagal, Largi and Chamera-I. It records that “no dam safety cell was created for implementation of the dam surveillance programme by any of the selected dam authorities” to respond to relief and rescue operations.

Dam safety: An overview

In the absence of dam safety cells, their functions, like review and analysis of available data on design, construction, operation, maintenance and performance of the structure, periodic inspections, surveillance and monitoring, safety evaluation, etc, are lying unfulfilled.

The health of dams and compliances to safety norms have become a lost priority, especially when the focus of the state government is on blindly pushing for more HPPs. On the one hand, amendments and dilutions in the Hydro Power Policy, 2006, are making the hydro sector receptive to more investment, while on the other, there has been a trend of falling profitability in the sector over the last eight years (Department of Economics and Statistics), where restoring projects after such accidents has been one of the major cause of escalating costs.

At the national level, in order to give legal backing to a stringent accountability and monitoring mechanism, to ensure continuous monitoring and surveillance of safety norms and operations, a Dam Safety Bill was drafted by the Union Ministry of Water Resources way back in 2010 and a revised version was even tabled in December 2018 in Parliament.

Environmentalists and experts studying dams have pointed out several loopholes in the current draft — the absence of public participation, a lack of transparency and accountability mechanisms and the problematic institutional structure for regulation headed by the CWC being some of the issues.

It is extremely disappointing that even this draft has met with opposition by some state governments given concerns like inter-state water sharing. Why is it that states do not treat safety regulatory mechanisms with the same priority as extracting and managing the resources? With no such mechanisms in place, how will projects be well-monitored, with the buck stopping somewhere, shifting the response to “prevention” as opposed to an “ad-hoc” approach?

It is a shame that policy-makers in Himachal continue selling the hydro dream, projecting the state’s “hydropower model” as an exemplar to be emulated, while they transfer the risks involved to the ordinary people of the state. It took the Vale Dam collapse that killed hundreds of innocents to force Brazil to pass a law on dam safety. The Himalayas saw escalated floods in Kedarnath in 2013 due to HPPs. In 2018, Kerala had floods due to water released from the Mullaperiyar dam. What is Himachal Pradesh waiting for now?

Vaishnavi and Yogesh work with the Himdhara Environment Research and Action Collective, Himachal Pradesh on the hydropower sector and Forest Rights Act, 2006