Ape-men of Flores: Gregory Forth talks about academia’s bias against testimonies of local people

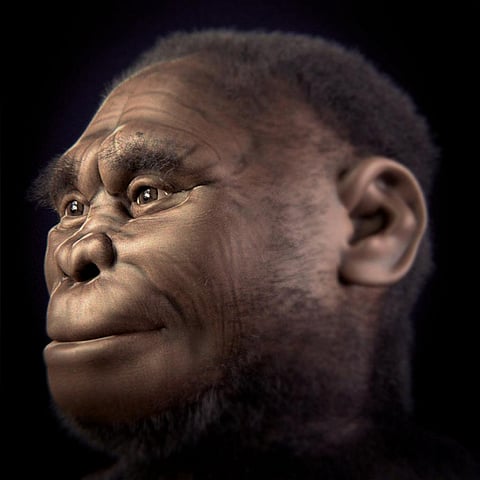

A facial reconstruction of the Homo floresiensis. Photo from Wikipedia

A group of scientists in 2004 announced the discovery of Homo floresiensis, a hobbit-like human ancestor on the island of Flores, Indonesia. Standing 3 feet 6 inches tall, these hobbits had relatively small brains, teeth disproportionately large to their body size, no chins and relatively large feet.

Gregory Forth, a retired professor of anthropology at the University of Alberta, Canada, began his investigations around this time on a mysterious species, which shared a striking resemblance with floresiensis in the Lio region of the island.

Forth’s new book, Between Ape and Human, documents this journey as he records statements from eye-witnesses and analyses them. Forth talks about his book and academia’s bias against investigations of mystery creatures based on testimonies of local people in a conversation with Down To Earth.

Rohini Krishnamurthy: How were you introduced to the ape-men of Flores?

Gregory Forth: I have been working on Flores island as an ethnographer, studying human culture and as a field anthropologist since the early 1980s, to explore the different ethnolinguistic groups inhabiting the island.

I first worked in central Flores, in a region called Nage. The people told me stories about tiny human-like beings that stood upright, walked on two legs and so on.

They were described as hairy-bodied and with no clothes on, sounding like they were physically more primitive than modern humans. However, according to them, they died out hundreds of years ago.

But then, in 2001-2003, I began working in the Lio region, which is the geographical focus of Between Ape and Human. The Lio people also told me about a similar kind of creature.

They had a special name for them: lai ho’a. They claimed they were still surviving, although very rarely encountered. Nevertheless, they were occasionally seen by people.

And then, in 2004, scientists found the remains of Homo floresiensis in the western part of Flores. I was lucky to hear about lai ho’a or the ape-men, as I call them, two months before the discovery and over a year before the announcement.

RK: You also describe yourself as an ethnozoologist. What does the job entail?

GF: Ethnozoology means understanding people’s knowledge of animals that inhabit their environment. One aspect of this is always comparing what local people say about animals, with a scientific understanding of those animals.

Often, they fit; other times, they don’t. But one aim of ethnozoology is to understand why people say what they say about animals and what propositions they make about them.

We interpret this local knowledge of animals through what we might call ‘cultural filters’.

RK: What are cultural filters?

GF: What local people say, can be extremely useful for guiding further research in academic science. I think several scientists would agree with me. After all, most species we know have been discovered after being first reported by ordinary people and not by academic scientists.

You can’t just take people’s accounts at face value. It has to be interpreted like any information should be.

I’ll give you an example. In Chapter two of my book, I describe the people who have never seen an ape-man, would describe them as having tiny tails. If this were true, they could not possibly be hominins (including all human species) and would have to be some kind of monkey.

The Lio people categorise any creature, not anatomically modern humans, as animals. For instance, one particular eyewitness claimed he had encountered a dead specimen of an ape-man. He said it had a tail. When I questioned him further, he acknowledged that he hadn’t seen the tail.

Another point is that some of the younger Lio people who have been to Borneo (an island politically divided between Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei) as labourers have seen gibbons or even orangutans (not found in the Lio region). They say these animals have a tail. But as you know, they don’t have tails.

Besides, there is also a notion in Lio and the Nage region that human beings grow a tail when they reach 90-100 years of age. This is why cultural filters are essential.

RK: Could you walk us through your analysis of eyewitness accounts?

GF: In the book, I go through various hypotheses and possibilities regarding what Lio people were telling me: What they’d seen and how they could be explained.

In fact, the first question I tackle is whether these are purely imaginary beings like we assume forest spirits to be. I spent a whole chapter showing that these creatures are not essentially supernatural beings in the same way the forest spirits are.

Some people describe particular familiar creatures — scientifically documented ones — as having a supernatural aspect. For example, I show that the ape-men are no more supernatural than creatures like freshwater turtles, which appear to be rare, which Lio regards as manifestations of spirits.

I even look at whether or not there might be an undiscovered ape in Flores, which is highly unlikely because this island sits to the east of Wallace’s Line, an imaginary line separating species found in Australia and Papua New Guinea, and Southeast Asia.

On the Indonesian islands east of Wallace’s Line, neither orangutans nor any other kind of ape occurs. To the west of it, you see the Asiatic biogeographic realm, including elephants, tigers and apes like orangutans.

I then consider whether we might be talking about humans, that ape-men could be some undescribed lost tribe. I am able to show in my book that this is unlikely.

So, I am left with the hypothesis that people have seen something that sounds very much like the reconstructions of the remains of Homo floresiensis or something about the same size, the same form, and possibly the same diet as how the Lio people described the ape-men.

RK: In your book, you argue that living or extinct species can remain hidden from science for a very long time. Why is it hard to document them?

GF: Extinct animals have very slim chances of being fossilised. It depends on the local geology and climate.

As for living species, academic scientists don’t go in search of new species. If someone finds one, scientists investigate it. Also, there are certain institutional barriers. Scientists are unlikely to win grants or funding based on testimonies of local people as this is not considered scientific evidence.

Finding a living species is also time-consuming. And then there are conventions. When species are identified through fossil bones, scientists assume they have died out. They ask: What is the point in going out and looking?

A well-known paleoanthropologist, John Hawks, from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, United States, argued that it was unlikely for a big animal like Homo floresiensis to have gone unnoticed.

But these ape-men are not so big and they live in forests. The most crucial point is that the local people have noticed ape-men. So, Hawks’ assessment is a little arrogant.

In the book, I have mentioned that freshwater turtles and giant crabs have never been documented on the island.

However, very good circumstantial evidence suggests that the turtles, which might be extinct now, may have inhabited the island at one or two locations in small numbers about 30-40 years ago. I made these arguments in three published international journals.

RK: Is it possible that ape-men, if they exist, remain hidden because of natural barriers in forests?

GF: Flores is a mountainous region and is difficult to get around. That explains why they have so many languages.

But if someone wanted to investigate whether Ape-men exist, it could be possible to do so with some success. It might be possible to find living specimens or remains of the species that matches the description made by the local Lio people.

It is also possible that a different biological explanation might be found. It is not so much about the physical terrain standing in the way; it is the culture of academia. It decides which project gets funded. And this, in turn, allows certain kinds of research to move forward.

Additionally, people might not be aware of my ethnographic findings or discoveries from Flores. One reason for writing this book is to tell more people about them. It is possible that the book could promote more interest among scientists.

RK: Can you recall any exciting experience that did become a part of the book?

GF: I could have written a much longer book. We have word limits and so on. But one thing that comes to my mind is that in western Flores, very close to where Homo floresiensis was discovered, I came across a structure, reportedly a mass grave of creatures sounding very much like the ones described by the people of Nage and Lio.

I got the attention of two paleoanthropologists. But they did not get very far in obtaining permits from local people. Because it turned out there was some land dispute between two people on who owned the land and, therefore, who had the authority to give us the permit.

Both sides were not particularly opposed to the excavation. It’s just that they could not settle this dispute. The whole thing became stalled. So, we don’t know if anything was buried there.

RK: You conclude that a latter-day floresiensis or another, similar and presumably related, hominin — appears to be the best explanation for the Lio ape-man. But you also say that this conclusion leaves you uncomfortable and that you have difficulty fully accepting it. Could you elaborate on why you feel that way?

GF: I am a participant in the culture of academia. I understand the argument I am making is controversial. I have received a few nasty emails from people saying I have done a great disservice to science and anthropology.

Some negative reactions were bound to come my way. I also understand this kind of inquiry on mysterious creatures is held in low esteem in academia. It is for these reasons that I felt a little uncomfortable. Nevertheless, the argument stands and the book stands.