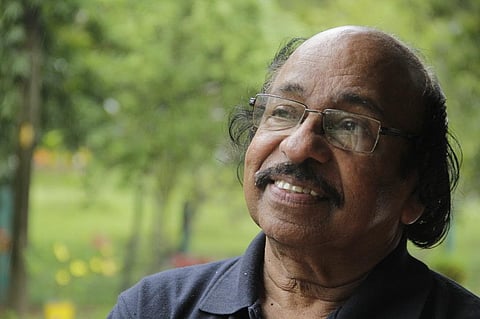

Ecopoetry is artistic resistance, says K Satchidanandan

K Satchidanandan, a renowned poet, critic, playwright, editor, columnist and translator, has always been vocal about the political dimensions of the looming environmental crisis. The poet, also a recipient of several awards, is the current president of the Kerala Sahitya Akademi.

Poetry for Satchidanandan is a dialogue with the self, others, nature and the universe. Greening the Earth, a recently released anthology edited by Satchidanandan and Nishi Chawla, offers a glimpse into our destructive relationship with the environment.

In a conversation with Down To Earth, Satchidanandan speaks profoundly on the capitalist idea of development and consumerist madness that leads to environmental degradation as well as ecopoetry and its role in climate activism. Edited excerpts:

Down To Earth (DTE): In the past you have talked about how nature poetry was not always taken seriously in the literary circle. Has that perception changed?

K Satchidanandan (KS): There was a time when nature poetry perhaps receded to the background, mainly because of a kind of critical perception that it was not sufficiently modern. And many believed that modern poetry should speak more about human beings, human condition, about war and what happened between the wars, nationalism, hatred and similar kinds of things. But nature has always been in poetry in some form, maybe as part of the human context or as objects to be described or presented to the readers.

Then again, even TS Eliot’s The Waste Land, with which modern poetry is supposed to have begun in the West, had a title which was nothing but a metaphor taken from the natural world. When you come to more contemporary poets, you find nature is returning to poetry in a big way. And that is because of a kind of modernistic eco-consciousness, which is perhaps different from the old nature consciousness that you found in the Romantic poets.

It is no more romantic; it is real because today, we have a real issue, the real issue of a loss of the natural kinship between nature and human beings. What has man done to nature? That is a major question today because we have created pollution; our greed has created or inspired a lot of consumption. It has led to the destruction of the forests, mountains and beings that exist around us. So, there has been a very negative transformation of relationship between human beings and nature. And in that context, a new kind of poetry, which can be broadly called ecopoetry, has come to be.

DTE: You have said poems on environment and climate crises, such as those in this collection, have taken a political dimension. How so?

KS: Yes, because there is a whole new politics which can be called eco politics, where environment becomes extremely important, and the preservation of the environment is seen as part of or as an attempt to preserve the human species itself.

So that is one aspect. Secondly, there is the question of who destroyed the environment. Of course, we can say human beings, but did all humans destroy the environment? Originally, it was capitalist greed that led to the destruction of the forests and the entire environment because the capitalist idea of development involves environmental destruction. Tribal people cared for the environment; that is why recently Noam Chomsky said we should learn from the tribals.

So these are the two aspects of politics I am speaking about. One, the larger eco-politics that comes out of the love of environment and second, a kind of resistance against the capitalist idea of development, which is at the root of the destruction of nature.

DTE: What is the role of poetry in climate activism?

KS: Poetry is not direct propaganda. It impacts the consciousness of our understanding of ourselves as well as our relationship with other people, with nature and the universe at large. It involves all these different levels of conversations. Through poetry, I am talking to myself, I am talking to other people, I am talking to nature, I am talking to the larger cosmos.

Poetry tells without telling so loudly and directly that perhaps we need to change our attitude to nature; we need to get over this consumerist madness. It tells us that we need to develop another idea of development. But it also involves the development of our own consciousness, of love, of peace, of a world that is greener and better than the world that our predecessors had left for us.

I have never claimed that poetry alone can change the world, but it can contribute to that change by creating and promoting consciousness. Ultimately, change can really take place only when activists and writers, playwrights, filmmakers, painters, sculptors and artists of all kinds come together.

DTE: How do you think forums like Kerala Literature Festival can mainstream the discourse on environmental protection?

KS: All the literary festivals, I think, now will have at least one of its themes on environment and nature. And as the director of the Kerala Literature Festival, I can assure you — because this is also one of my very, very primary and fundamental concerns — that maybe the next festival will mainly focus on this question of environment and the relationship between human beings and nature.

DTE: Who do you think are some of the important ecopoets?

KS: There are a lot of Indian poets, right from somebody like Shankha Ghosh to too many poets in many languages. In Malayalam, for example, Sugathakumari was one of the major beginners of a new kind of nature poetry. Nature is a major theme in her poetry. Not just describing nature, she is but also worried about what is happening to nature and what human beings have done to nature. Remember, she was an environmental activist and a poet at the same time.

In the works of Malayalam poets before Sugathakumari, Vyloppilli Sreedhara Menon, Edasseri Govindan Nair, P Kunhiraman Nair, etc., nature was always there. But later, a kind of new awareness of nature, which is combined with environmental consciousness, was visible.

Then there are other young poets of today, such as MP Pratheesh and Dona Mayura, who even use objects from nature as part of their poetry. You can call their works poetic installations or object poetry. Sometimes they use water, stones or leaves. They write lines connecting these objects with human existence.

DTE: In many platforms you have said it is time to change human priorities. How can that be done in consumerist societies?

KS: The priority of governments today seem to be a kind of fast development, which promotes consumerism, developing capital and creating more wealth. And there are other concerns like a narrow kind of nationalism, a very reductive kind of patriotism which produces more hatred towards certain people and nations than love for the country. Then, of course, there is religion, from which all spirituality has been completely erased and turned into communalism, another source of hatred.

What is happening in the ‘communist’ countries of today has very little to do with what was originally meant by communism, where nature was very important, the relationship between human beings and nature was important, and equality was important.

Speed is the ecstasy of the new world, as Milan Kundera wrote in his book Slowness. He speaks about those times when life was slower and when we could lie down under a tree and watch the windows of the sky opening and read a poem very leisurely, line by line, word by word. Perhaps we need to recapture some of that slowness, leisureliness and meditativeness that we had earlier.

We have all kinds of new technologies and want to be faster. Let us have a very balanced kind of attitude toward science and development so that they can be used productively. But always remember, science devoid of ethics can be a terribly destructive force.

So the emphasis on ethics is extremely important, and even when we discuss problems of the environment, what has destroyed the environment has something to do with our loss of values, our loss of primary ethics. Living beings, including their bees, butterflies, trees, and all other beings on earth should coexist. They are the inheritors of the earth. I am using the title of a famous short story by Vaikom Muhammad Bashir, Bhoomiyude Avakashikal. So we are not the only inheritors of the earth.

The earth is inherited by all these beings, and this realisation should make us humble and make our scientists also realise that without a basic sense of values, science can just destroy human rights, destroy the earth.

This was first published in the 16-30 June, 2023 print edition of Down To Earth