A new study by the Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur (IITKGP) has found new evidence for the popular hypothesis that climate change caused human migration during and after the collapse of the Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC).

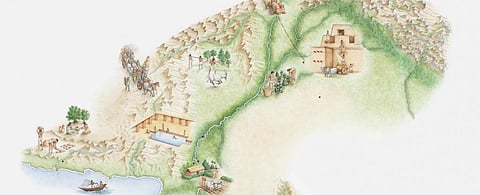

The researchers concluded this from the study of two previously unknown post-Harappan, Iron Age sites in the western part of the Great Rann of Kutch (GRK) and the lower fringes of the Thar desert.

The Iron Age (3100-2300 years before now) is often referred to as the ‘Dark Age’ because of scant historical and archaeological evidence from that period. These are the first Iron Age sites found in this particular region.

The evidence from the sites at Karim Shahi in the GRK and Vigakot in Thar proves that human habitation continued in the region up to the Early Medieval Period (900 years before now).

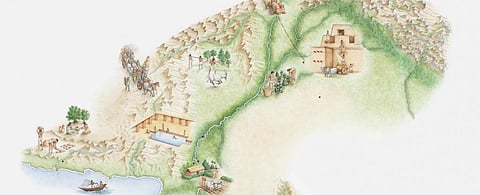

The study published in the journal Archaeological Research in Asia brought together evidence from archaeological remains like unearthed pottery, historical anecdotes and paleoclimatology to establish that the inhabitants of the IVC slowly moved from the Indus valley sites in the west into the Ghaggar-Hakra valley in the east.

“Our findings suggest that such human migration was far more expansive than thought before. We believe that the gradual southward shift of Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) over the last seven thousand years forced people to migrate for greener pastures,” Anindya Sarkar, lead author of the study and professor of geology and geophysics at IITKGP, said.

The shifting of the ITCZ decreased monsoon rains and led to the drying up of rivers which would have made agriculture rather difficult.

But the sites in Karim Shahi and Vigakot show evidence of continued existence of river systems and regular rainfall right until when the Persian traveller and scholar Al Biruni visited Kutch. He documented the river Mihran flowing into the sea at two places — the city of Loharani and a place called Sindhu Sagar.

This was backed up with evidence from the analysis of sediments, pollen and oxygen isotopes in fossil molluscan shells retrieved from the sites. The inhabitants of these sites were traders throughout the time and traded with far-off civilisations in Persia and China, according to Sarkar.

The human migration from the IVC is very similar to the one that will take place from regions impacted by the consequences of human-induced climate change, especially low-lying coastal regions and islands which often bear the brunt of the extreme weather events and sea level rise due to global warming.

Back in 1990, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change had noted that the single greatest impact of climate change will be on human migration. Experts believe that by 2050, more than 200 million people will be forced to leave their homes and become climate migrants or even climate refugees but this number is highly uncertain.

This is because people move their place of habitation because of a wide variety of social, political, economic and other environmental reasons which are all interconnected and it is difficult to delineate one from the other, according to the report Climate Change, Migration and Displacement published by Overseas Development Institute and United Nations Development Programme in November 2017.

It also stated that in 2016, about 24 million people were instantly displaced by the sudden onset of climate events like cyclones and floods but there is very little evidence to inform about the number of people migrating due to slow onset events like drought and desertification.

The evidence for such climate change-based migration is slowly surfacing.

For instance, between 2011-2015, climatic changes like severe drought-induced conditions led to armed conflict, which in turn, led to asylum seeking and migration, according to a research paper published in the journal Global Environmental Change in January 2019.

“The effect of climate on conflict occurrence is particularly relevant for countries in Western Asia in the period 2010–2012, when many countries were undergoing political transformation,” says the study.

“This finding suggests that the impact of climate on conflict and asylum seeking flows is limited to specific time period and contexts,” it further adds. Further work in this regard is required to identify climate migrants and refugees already living among us.