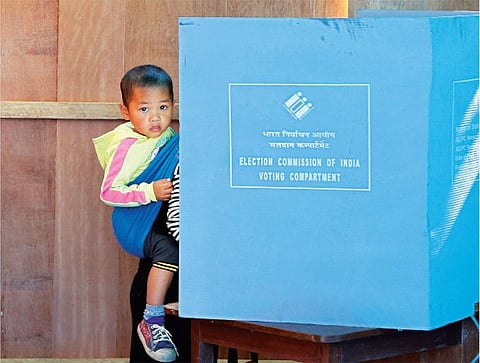

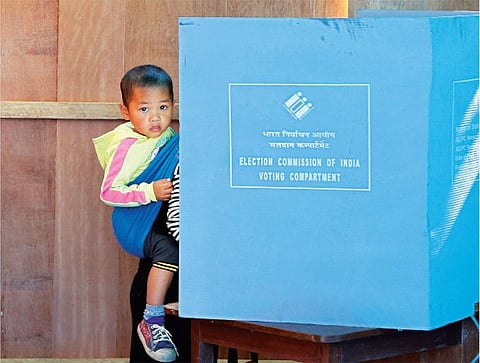

India is at an electoral juncture. Over the 12 months between 2018 and 2019, the voter size in the country would swell by a record-breaking number of 52.6 million. This increase is because of the post-Millennials—also called Centennials or Generation Z— the ones born at the dawn of the 21st century. They have come of age at a crucial time—seven states went to polls in 2018, while another six assembly elections, the 17th general election and several elections to local bodies are due in 2019. The wisdom and foresight of these 52.6 million first-time voters will play a major role in deciding whether India’s polity will be founded on peace, equity and cultural diversity or on religion, casteism and fanaticism. Clearly, a great deal is at stake. Particularly at stake are the ideas of equality, justice, fraternity and freedom enshrined in the Constitution. But have we managed to raise these neo-voters as responsible citizens? Let’s do some introspection.

To begin with, our education system lacks in the vision that would have equipped the youngsters with logic, rationale and the ability to argue and discern and engage in a debate. According to the Annual Status of Education Report (aser) 2017, 28 per cent boys and 32 per cent girls drop out of school even before completing their secondary education. In Madhya Pradesh alone, 4.2 million children dropped out of school between 2010-11 and 2015-16. Moreover, 96 per cent children enrolled in 12th class do not benefit from the s k i l l de v e l opme n t programmes in the curriculum which can at best make one skilled enough to work in fields or enterprises like tourism, car-repairing and call centers. Emphasis on skills that can enable one to become independent entrepreneurs and on educational content relating to Constitution, citizenship, camaraderie, idea of empathy and human values that are necessary to make our children cognisant are missing from the curricula altogether. aser-2017 report further notes that more than 70 per cent children in the age group 14-18 use mobile phones but one-fourth of them cannot read the content written in their own language.

Unfortunately, their wisdom largely appears to have been shaped by the media hegemony. A cursory glance at headlines over the last 18 years shows that almost 75 per cent of news reports are on terrorism, caste-and-communal violence, mobocracy, starvation and malnutrition deaths, manifestation of agrarian crises as farmers’ suicides, crony capitalism and deep-rooted corruption. The post-Millennials have already witnessed the fall of our polity. Now, they are learning the grammar of violence. They have started taking abusive language, blatant falsities, malice and malevolence, intolerance and corrupt practices as the rudiments of our democratic system. There has also been a radical change in the social fabric of our country over the past two decades. With the disintegration of joint family system, family members have rarely been available to handhold the new generation while the impressionable kids enter teenage. Worse, high economic inequality has affected the development of most of these youngsters.

According to Forbes, there were four billionaires in India in 2001; their breed surged to 101 in 2017. A paper, titled Indian Income inequality, 1922-2015: From British Raj to Billionaire Raj?, published by the World Inequality Lab at the Paris School of Economics, says although India prospered financially between 1980 and 2015, its development was lopsided. The extent of this lopsided development can be gauged from the fact that during the 35 years, the income of India’s bottom stratum, comprising 397 million adults (50 per cent of the country’s adult population), grew by 90 per cent, whereas that of the 7,943 people (or, 0.001 per cent adults) in the top wealth echelons increased by a whopping 2,040 per cent. The disparity becomes clearer when one compares their average income. In 2015, the average annual income of the Indian adults, who were in the bottom stratum, was just `40,671, whereas that of the uppermost echelons was `18.86 crore. Not to forget, over one-quarter of the 52.6 million children belong to the vulnerable communities like Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Can children who have grown amid such huge disparity make the right choice and participate well in the democratic process? Doubts do not end here, and for a reason.

Raised on malnutrition

The 52.6 million neo-voters have escaped untimely death in a country where under-five mortality and neonatal mortality rates are depressingly high. According to an estimate, 20.5 million under-five children have died between the beginning of the century and 2017-18. These children could have been potential voters today. But not all of those who have survived remain unscathed. In 2000-01, nearly half—47 per cent—of children under five years of age were underweight (low weight for age and height); 45.5 per cent “stunted” (low height for age) and 15.5 per cent suffered from “wasting” (low weight for height), according to the National Family Health Survey (nfhs)-2, conducted in 1998-99. According to Unicef, stunting is caused by long-term insufficient nutrient intake and frequent infections. Its effects, which includes delayed motor development, impaired cognitive function and poor school performance, are largely irreversible. Wasting, which is usually the result of acute significant food shortage and/or disease, is a strong predictor of mortality among children under five.

In 2008, The Lancet published a series of papers on maternal and child malnutrition. One of these papers, titled Maternal and Child Under nutrition: Global and Regional Exposure and Health Consequences, shows that the condition of being increasingly underweight as per age poses a dire threat of death on account of diarrhoea, pneumonia, malaria and measles. Of the states that went to polls in 2018, Madhya Pradesh has 42.8 per cent of children suffering from underweight; in Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan, 37.7 per cent and 36.7 per cent children are underweight. Anaemia, which is usually associated with malnutrition, was prevalent among 74.3 per cent of children in 2000-01. Though the rate has reduced to 58.6 per cent now, according to nfhs-4 (2015-16), the percentage of anaemic children in Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh is an astounding 68.9 per cent, 60.3 per cent and 41.6 per cent.

In the past 20 years, disease burden due to malnutrition has increased rather than declining. Undernourishment lowers the immunity system of children, making them prone to severe infections and raising the risk of mental retardation and child mortality. Though mother’s milk has been given its due importance in the Indian tradition and popular Indian cinema, we have not made any noteworthy progress in promoting exclusive breastfeeding, which can single-handedly bring a 20 per cent reduction in child mortality.

Almost half of our neo-voters remained deprived of this chance. And a prime reason for this could be the collusion between the politicians and multinational corporations to promote packaged baby foods. Likewise, as soon as a child attains the age of six months, they should be given an appropriate supplementary diet along with mother’s milk well up to two years. Although, the government spends a fortune promoting the practice, only 42.7 per cent children have access to complementary food. The figure was 33.5 per cent two decades ago.

Victims of injustice

Preamble to the Constitution of India proclaims, “We, THE PEOPLE OF INDIA, having solemnly resolved to constitute India into a SOVEREIGN SOCIALIST SECULAR DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC and to secure to all its citizens JUSTICE, social, economic and political.” Now the moot question is whether our children are getting their due? As per nfhs-4, every fourth Indian child gets married at an early age—the figure translates to 26.8 per cent of children in the country. In Bihar, 42.5 per cent girls are married off before they turn 18; the figures are 34.4 per cent in Rajasthan; 32.4 per cent in Madhya Pradesh; 21.3 per cent in Chhattisgarh; and 21.1 per cent in Uttar Pradesh.

These girls rarely receive proper education; they fail to become self-dependent; and they enter into motherhood before time. And this affects their health. But our politicians rarely raise a clarion call against child marriage. In fact, they use marriage functions as political tool. In Madhya Pradesh, the government has introduced the Mukhyamantri Kanyadan Yojana which, in a sense, encourages the practice of dowry and gender discrimination. How can such a voter exercise well-informed franchise? At many a places, these neo-voters toil as bonded labourers. As per the Census 2001, 12.7 million children in the country were working as child labourers. Although, the trend is on the wane, independent estimates show that the country still has 10.1 million child-labourers. But no official data is available on this as the state machinery has not carried out a systematic survey on child labour in the past 20 years.

The 21st century has not provided any rights of safety, dignity and protection. At the beginning of the century, 10,814 cases of crime against children were reported. The latest National Crime Records Bureau report shows that number of such cases has increased by 10 times—106,958 cases of crimes against children were reported in 2016. In Madhya Pradesh, such cases increased from 1,425 to 13,746; in Rajasthan, it increased from 218 to 4,034; in Chhattisgarh from 585 to 4,746; in Uttar Pradesh, from 3,709 to 16,079. The number of pending court cases pertaining to crimes against children has also increased by 10-fold—from 21,233 in 2001 to 227,739 in 2016. In 2011, some 2,113 cases were registered for rape and sexual exploitation against children; it subsequently saw 18 times increase over five years—36,022 in 2016. In 2017 alone, 2,100 cases of sexual exploitation of children were reported from 19 juvenile homes of seven states.

In such a grim scenario, how do our neo-adults view our legislature, judiciary and executives? After all, these three pillars of our democracy are partners in this crime against children. They would be responsible if these neo-voters make any wrong choice while exercising their franchise and put the nation and its sovereignty at stake.

(Sachin Kumar Jain is an Ashoka Fellow and founder secretary of Vikas Samvad)

RESOURCES