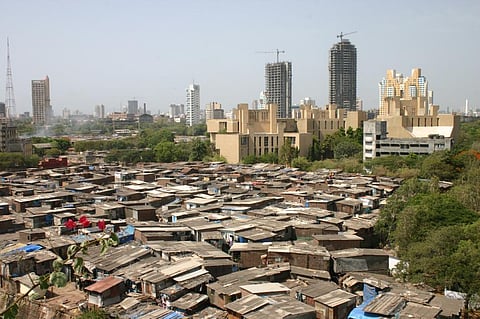

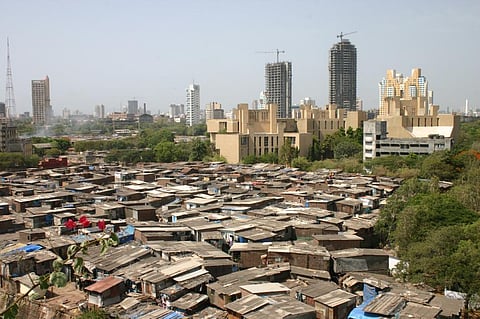

In 2017, 73 per cent of the wealth generated went to the richest one per cent in India. Their wealth increased by Rs 2,091,300 crore, which was the total budget of Central Government in 2017-18. The country added 17 new billionaires to the list, taking the total to 101. Their collective wealth increased by Rs 489,100 crore—from Rs 1,577,800 crore to over Rs 2,067,600 crore. These were the findings of the Oxfam report.

Interestingly, in the same year, 67 crore Indians, comprising the poorest half of the population, saw just one per cent increase in their wealth. It is no surprise then that India is the second most unequal region in wealth distribution, as revealed by the World Inequality Report 2018.

In 2016, income of 273 people was more than that of 2.2 crore people

The disparity becomes evident when one looks at the gross total income of about 4.5 crore tax payers for the assessment year 2015-16 as mentioned in the Income Tax Return Statistics released by the Central Board of Direct Taxes. Total income of about 2.3 crore (2,29, 52,645) people, who fall under different income categories (less than Rs 150,000 per year, between Rs 150,000 and Rs 200,000, and Rs 200,000 and Rs 250,000), was Rs 556, 835 crore. This is still 10 per cent less than what just 273 people earned in the same assessment year. Each of them earned at least Rs 500 crore, taking their total income to Rs 618,459 crore.

During the same period, about 27.5 per cent of India’s population was identified as multidimensionally poor and 8.6 per cent of the country’s people lived in extreme poverty, according to the 2018 Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI). In almost every state, poor nutrition is the largest contributor to multidimensional poverty. The index also revealed that India still has 364 million people living in poverty—the highest number in any country. It is more than 25 per cent of 1.34 billion people living in ‘multidimensional’ poverty globally.

Why this wealth inequality?

“Economic inequality is largely driven by the unequal ownership of capital, which can be either privately or public owned,” observes the World Inequality Report. “Since 1980, very large transfers of public to private wealth occurred in nearly all countries, whether rich or emerging. While national wealth has substantially increased, public wealth is now negative or close to zero in rich countries. Arguably, this limits the ability of governments to tackle inequality; certainly, it has important implications for wealth inequality among individuals,” the report argues.

To truly understand the scale of wealth accumulation, one needs to look at tax havens. The wealth held in tax havens represents more than 10 per cent of global GDP. Dramatic increase in percentage of global wealth held offshore is making it difficult to assess and tax wealth and capital income in a globalised world. While land and real-estate registries give some idea of wealth accumulation, they do not count a large share of the wealth, which is in the form of financial securities. Besides data transparency, changes are needed in national and global tax policies as well as wage policies to address global wealth inequality.