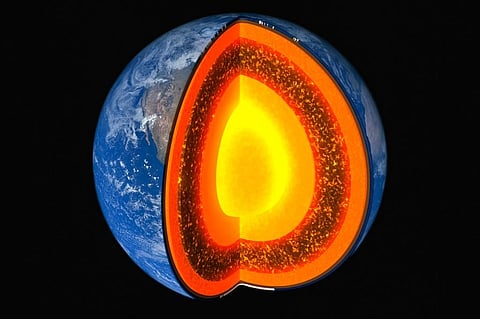

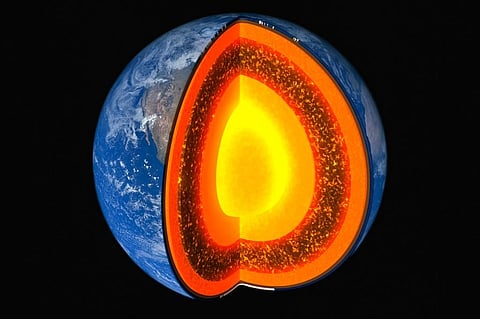

The mantle — a 2,900 km thick layer of solid rock sandwiched between the Earth’s upper crust and lower core — has been hiding two layers, two new research papers revealed.

One is the “low viscosity” zone in the upper mantle, roughly 100 kilometres in thickness, according to a study published in the journal Nature on February 22, 2023.

The upper mantle extends from 40-410 km depth. The temperature here ranges from 1,000-3,500 degrees Celsius.

The other layer is the low-velocity zone, which is also a part of the upper mantle. Though this layer is not new, a Nature Geoscience paper found that it is a semi-global feature, distributed around 44 per cent of the Earth.

Junlin Hua, a postdoctoral fellow at the Department of Geological Sciences, The University of Texas at Austin, told Down To Earth:

The 44 per cent figure, including both continent and ocean, is likely underestimated. This is because the ocean is relatively less sampled.

“The mantle makes up the largest part of Earth, there’s still a lot we don’t know about it,” Sunyoung Park, a geophysicist with the University of Chicago and the lead author of the study, said in a statement.

In the Nature study, Park and colleagues studied deep earthquakes, which occur at 300-700 km depth.

Deep quakes are less-studied than their shallow counterparts. As these seismic waves reach the mantle, they could reveal more information about it, the researchers speculated.

They studied the 2018 Fiji earthquake of 8.2 magnitude, using Global Positioning System (GPS) sensors. They measure the earthquake’s size based on the displacement a satellite receiver station suffers.

Their analysis showed that the Earth kept moving months after the earthquake. “You can think of it like a jar of honey that slowly comes back to level after you dip a spoon in it — except this takes years instead of minutes,” said Park.

The team deduced the mantle’s viscosity (a material’s ability to resist flow) based on the observed deformations.

A roughly thin layer — 100 km in thickness — stood out. Sitting at the bottom of the upper mantle, it was less viscous or runnier than the rest. This layer could be a global feature, the authors speculated.

The low viscosity zone coincides with the transition zone between the upper and the lower mantle, Jean-Philippe Avouac, one of the study’s authors, told Down To Earth. The lower mantle extends from 660-2,700 km.

This transition zone was already known, the expert said. But their study documented the viscous properties of that transition zone.

“This is an interesting new study and really provides some important insights,” Hua explained. He was not involved in the study.

Further, the researchers think this layer likely affects how Earth transports heat and mixes materials between the crust, core, and mantle over time.

The mantle’s viscous properties govern convection — the transfer of heat between areas of different temperatures. This enables plate tectonics, Avouac highlighted.

“Mantle convection results in the transport of rocks and heat,” he added.

The viscosity of the rocks in the transition zone between the upper and the lower mantle determines whether a plate sinks below another one (subduction) through it. This, according to the expert, could result in the mixing of the upper and lower mantle.

Hua initiated his Nature Geoscience study after analysing the low-velocity zone beneath Turkey.

Hua and his colleagues analysed seismic waves — shockwaves released after earthquakes — from across the globe to study the mantle.

Seismic waves act like CT scans, allowing researchers to ‘see’ the Earth’s interiors. They behave differently as they pass through different materials. For example, they travel slower when they pass through hot materials.

The waves travel slower in this layer, suggesting a higher temperature. “We need to have a partial melt to explain the speed we actually observed,” Hua explained.

Their analysis showed that the partially molten layer extends from 90 km to 150 kilometres. Below this depth, the waves resume speed.

This layer sits below the tectonic plates, which create new crusts and destroy older ones. Plate tectonics is thought to have played an instrumental role in making the Earth habitable.

Their study also shows that the melt in this layer does not appear to influence plate motion. “When we think about something melting, we intuitively think that the melt must play a big role in the material’s viscosity,” Hua said in a statement.