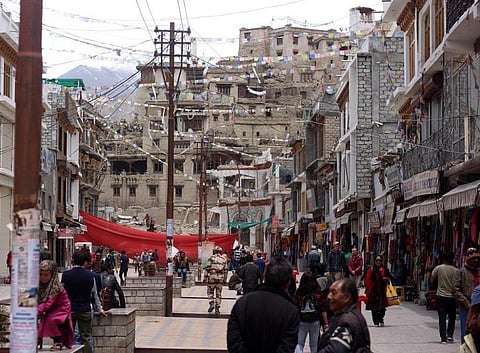

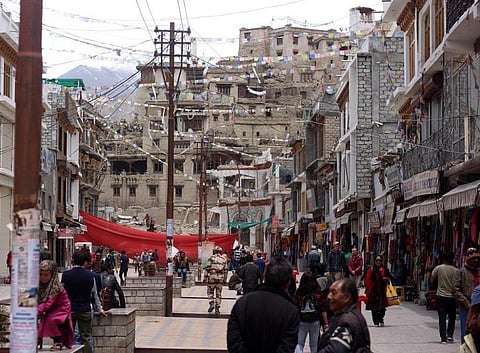

Ladakh is the last Shangri-La—an earthly paradise isolated from the world and permanently happy. But problem has started brewing in this paradise. Dry taps and tube wells and a possibility of a prolonged water crisis is casting huge shadows on its present and future. Leh, its largest city, has started rationing water—two hours in the morning and in the evening— from this month. Other parts of Ladakh region are no better.

What Shimla suffered little more than a month back, Ladakh may experience in the coming months; and much of it is its own making. In 2017, a ‘record’ 277,000 tourists visited Ladakh—a region with a native population of about 274,000. Previous year, number of visitors was more than 230,000. While it may be overwhelming to know that the number has increased from just 527 in 1974 (when Ladakh was opened to tourism), one must know that in the same year (2016), Ladakh recorded one of the lowest rainfall years, receiving just 20.9mm of rain as opposed to the annual average precipitation of 100mm.

Number of tourists continues to increase, but volume of precipitation dips

The land of high passes counts on its annual precipitation, mainly snow, but between 2013 and 2017, it has received between 50 per cent and 80 per cent deficit in annual precipitation for four consecutive years, with 2017 breaking the spell of deficit rain.

This is not enough to sustain the locals and the growing tourist population, especially when the latter is more wasteful. According to a study by the Ladakh Ecological Development Group (LEDEG)—an environmental NGO based in Karzoo (Leh)—an average Ladakhi uses 21 litres of water per day during summer and 10-12 litres during winter, while a tourist needs as much as 75 litres.

Tsering Angmo, deputy director of Jammu & Kashmir Department of Tourism had told media that every year, 25-30 guest houses are getting registered in Ladakh with the total number of hotels and guesthouses reach 826 as of November 2017. They have 13,732 beds. Besides this official number, there are several other home stays that are not registered.

If we consider double occupancy for each bed, a back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that on a given day, assuming all the registered accommodations have full occupancy, Ladakh would need 2.5 million litres (20,59,800 litres) of additional water to survive.

“Before 2005, Ladakh used to receive mainly foreign tourists. Their number was restricted to 25,000-30,000 each year. But after that, domestic tourists started coming in large numbers,” Tsering Sandup, executive councillor (Tourism) at Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council tells Down To Earth. Domestic tourist arrival grew by 43 per cent and foreign tourist arrival by 28 per cent between 2015 and 2017.

Change in water use

With growing water demand and drying up of common taps, locals have long resorted to digging borewells. “Almost all the households, hotels and guesthouse have their own private borewell and there is no regulation on it. All the springs within Leh town have dried up and, we believe it is the impact of ground water exploitation. The question will not just stop at number of borewells but how much water they extract from the ground. It requires a comprehensive study,” Nordan Otzer, executive director, Ladakh Ecological Development Group tells Down To Earth.

While the study by LEDEG points out the different water use pattern among locals and tourists, Sandup believes that even locals have started consuming more water than what they used to do a decade ago. “Weather is getting hotter, forcing people to increase their frequency of taking baths,” he adds. Sandup is not far off the mark as the temperature in Ladakh increased by 3°C between 1973 and 2008, while in the rest of India it increased by only 1°C, as confirmed by Jayaraman Srinivasan of the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore. She is one of the authors of the periodic reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

However, weather, alone, must not be blamed for the changing water use. “There is a tendency among locals to adapt to certain practices adopted by tourists. We have witnessed that in certain wards where water supply is consistent people have installed modern sanitation facilities in their households,” adds Otzer.

With the glacier on which Leh depends is likely to melt completely in the next five to six years, the demand for water is predicted to grow to 6 million litres by 2019 and volume of precipitation witnessing a southward trend, visitors to Ladakh has to act responsibly and reduce water usage. The least they can do is choose hotels or guesthouses with traditional dry Ladakhi compost toilets, take shower less often and for less time, and “remember that you are in a desert”.